This place will lend you books for free

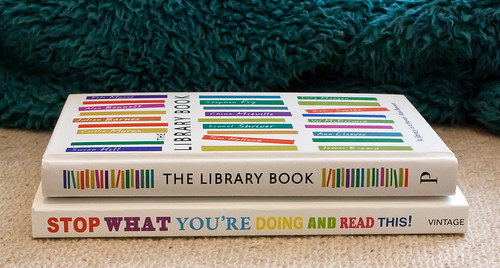

The Library Book

edited by Rebecca Gray

This collection of essays, musings and stories about public libraries has been compiled in support of the Reading Agency‘s library programmes. Which is definitely a cause I can get behind. They are all big names, from Zadie Smith to Alan Bennett to Susan Hill to Stephen Fry, but sadly the levels of enthusiasm and quality are a little variable.

I think part of the problem is that several of the essays cover the same ground: memories of the writer’s first library followed by a vociferous attack on the idea of closing any of them. Some writers are more practical, looking at how libraries and librarians can change with the times. Seth Godin makes a good case for the necessity of the librarian as gatekeeper of information. Bella Bathurst talks about libraries as places where people can mix, can make connections, can interact, whoever they are.

Other writers use fiction, including a very nice extract from China Miéville’s novel Un Lun Dun (though I can’t help think that’s cheating, when everyone else seems to have written their contribution specially). And I like that not all of the writers are novelists. There are also several journalists and, my personal favourite, Nicky Wire, whose piece is titled “If you tolerate this…” and discusses (among other things) the background behind that great Manic Street Preachers lyric “Libraries gave us power”.

This book is certainly a conversation-starter. Though my position on public libraries was never in dispute, I have learned more about the potential arguments against spending public money on them and gained many weapons in the arsenal against such attacks.

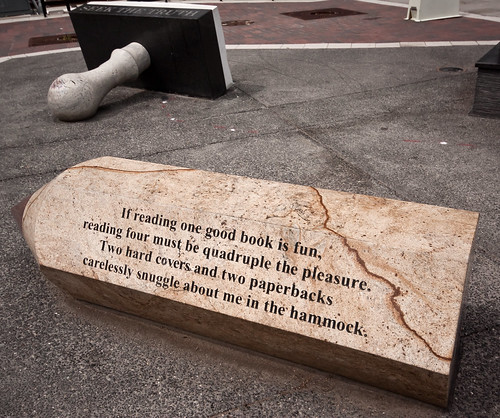

I love libraries. To me, these days, they share much in common with bookshops, in that I’m stepping into a room crammed full of books and I get to take some home with me. But then these days I can afford to buy enough books to keep up with how much I read. When I was a child I read so, so much more (and admittedly the books were smaller, generally) and neither I nor my parents could have afforded that without the local library. But libraries are about more than just reading. They are community centres. They are public access to the internet. They are free access to information. They are equal access to culture. They are great.

Published 2012 by Profile Books.