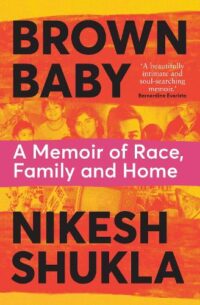

Book review: Brown Baby by Nikesh Shukla

Just when I’ve got used to the recent trend of memoirs written in the form of a series of essays, journalist and novelist Nikesh Shukla adds a new twist in his book Brown Baby. While each chapter takes a different topic from his own life, they are not essays but instead letters to his eldest daughter, affectionately nicknamed Ganga.

Just when I’ve got used to the recent trend of memoirs written in the form of a series of essays, journalist and novelist Nikesh Shukla adds a new twist in his book Brown Baby. While each chapter takes a different topic from his own life, they are not essays but instead letters to his eldest daughter, affectionately nicknamed Ganga.

Except that his daughter is still young (under 10, I believe) so she most likely won’t be reading this book for a while yet. It’s certainly not written as though it’s intended for primary-school-aged children and Shukla acknowledges a few times that his intended audience won’t be his first reader, that she will come to it in several years’ time, if at all.

So why this format? It’s a hook, of course; not many books are written in second person. And it was probably a useful exercise for Shukla to organise his thoughts when approaching writing this. But it does also add a layer of meaning for us readers who aren’t children of Shukla’s. Initially it feels intrusive, like this is genuinely a personal letter from a father to a daughter, in which he opens up to her for possibly the first time. But once I got past the feeling I was eavesdropping, I think the format made this more impactful.

As the chapter titles in the format “How to talk to you about…” suggest, what Shukla is exploring here is how to talk to his young daughters (he has two, though the book is specifically addressed to the elder of them) about some of life’s biggest, hardest topics. These include racism, being the child of immigrants, feminism, being an LGBTQIA ally, climate crisis, anxiety and depression. All told through the lens of his grief following the death of his mother.

“Ganga, I used to assume that tantrums were a child’s overreaction, an inability to control your emotions despite low stakes…But…When I think about my friends who have boys, they’re always cross or grumpy or moody or sensitive. We never refer to them as having a tantrum.

It’s hard to delete words so casually ingrained into your brain from everyday usage. Language is often careless in this way. Language is learned more than it is considered…How society has added baggage to language needs to be acknowledged. Words are not free of history.”

Shukla’s tone is informal and confessional. He balances emotionally raw moments with humour; specific, detailed moments from his own life with abstract musings. At times it’s a little rambling and can be repetitive, but the overall effect is warm and open.

Like most people who are smart and introspective, Shukla is frequently uncertain of himself. Sometimes a situation comes up and he isn’t sure he’s dealt with it in the right way, but it later turns out it was. For instance, one of the most impactful passages for me is when his daughter insists her skin is dirty because it’s brown. She doesn’t want to play with brown dolls or hear from her father that brown is beautiful. For Shukla this brings back the years of schoolyard bullying he suffered. But several months later, his daughter is playing with brown dolls and tells him she is proud of her skin colour. Shukla isn’t certain what changed her mind. Perhaps it was reading her books with brown lead characters, or gently repeating that her colour is beautiful. Perhaps it was nothing to do with him.

Shukla returns a few times to his unhealthy eating habits. He knows they’re unhealthy. He knows he is using food for the short-term pleasure, to keep his sadness and anxiety at bay. But he doesn’t know how to change his habits. In this case there is no neat resolution before the book ends. I’m not sure it constitutes useful advice for his daughter but it certainly strikes a chord memoir-wise.

In perhaps my favourite chapter, Shukla recalls the first year or so of his daughter’s life when he would take long walks around Bristol, carrying her in a sling, to get her to sleep for a few hours. Shukla was new to Bristol at the time, so it also served as an introduction to this city that I love dearly. He describes locations I know well, though of course from his perspective they’re not quite the same. Having moved here from London, he found Bristol very, very white. So, though he isn’t religious, he found himself walking to the mosque in Totterdown (just a few streets from my house) around sundown, to be briefly surrounded by brown faces.

In the book’s most surreal moment, Shukla describes walking with his baby daughter around Stokes Croft (where I first lived in Bristol) in the early hours of the morning. The nightclubs are emptying out their last stragglers and a group of young women approach Shukla. After a brief exchange, they bow to his brown baby in that combination of solemnity and ridiculousness that happens when you are young and drunk, high or both. It’s a little touching and very odd.

I guess it was serendipitous that I read this volume that is above all an introspective examination of family at a time when I too was (and still am) thinking more than usual about family, in the wake of my grandad’s death. I think part of grief, for me, is an attempt to understand what has been lost and what remains in the form of memories. Shukla dealing with own version of that same question helped me articulate my thoughts, for which I am very grateful.

I read this as part of my work book group and we had quite diverse views on it, but we did share one concern. Shukla’s wife is almost entirely absent from this book. This is probably something they agreed between them for their own reasons. But it does have the unfortunate effect of making Shukla’s debates about parenting decisions sound like solo efforts, as though he’s a single parent or his wife has no opinion to offer. This is particularly odd in the chapters where he addresses gender and feminism. While I applaud his willingness to discuss periods and puberty when the time comes, he does have a co-parent he can turn to for insight – a fact that isn’t always clear in this book.

But overall this is a good read, a soul-searching, emotionally raw text.

Published 2021 by Bluebird.

Source: Borrowed from a friend.

One Comments

Comments are closed.