Watching the vanishing sunset against the deepening blue

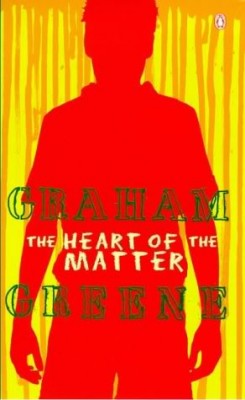

May We Be Forgiven

by A M Homes

This is a strange book that at first I – not exactly struggled with, but I did wonder if I should be engaging with it more. A lot happens and it covers quite a range of issues, but with a sense of humour and fun that kept me reading on.

It’s the story of a year in the life of Harry, a middle-aged history professor who has an obsession with Richard Nixon and, at the start of the book, a wife he seems to have no emotional engagement with. After Harry’s brother George has a car accident that leaves him mentally unbalanced and a young boy orphaned, Harry’s life changes out of all recognition, as does he.

“Was there ever a time when you thought – I am doing this on purpose, I am fucking up and I don’t know why.”

The book is very fast-moving to begin with, in fact I realised on page 20 I’d missed something huge even as another huge event was happening, but the bulk of the book is about the fallout from those events and the pace settles down.

Similarly, to begin with Harry’s narration is odd and unengaging but he gradually becomes a warmer character. If I were to summarise his story arc it would probably sound trite or possibly even soap-opera-like, but it’s actually funny and nuanced and, for the most part, feels real. The book deals with death and grieving, mental illness, loneliness, third world aid and the vulnerability of both children and old people. But it’s a pretty chunky book so there’s plenty of room to explore those issues without it getting too heavy.

“‘Were we always Jewish?’ Ashley asks.

‘Yes.’

The ceremony concludes, and one of the guests turns to me and says, ‘Given the circumstances, I think the rabbi did a very good job. What did you think?’

‘It’s my policy not to review funerals.'”

The humour grew on me as I got used to Harry, and was sometimes surreal, though it was also sometimes crude. And while Harry became a warmer character, I’m still not sure I really liked him by the end. I certainly cared how things turned out for him, which I guess is what matters.

“There’s something wonderfully melancholic about being outside on a spring evening watching the vanishing sunset against the deepening blue; the outlines of the old thick trees, full of bright fresh leaves, the surprising, gentle tickle of a breeze, and it somehow feels so good to be alive.”

Published 2012 by Granta Books.

Winner of the Women’s Prize for Fiction 2013.

Source: Amazon.