We love breasts, yet we can’t quite take them seriously

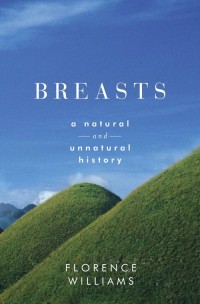

Breasts: a Natural and Unnatural History

by Florence Williams

Continuing with the popular-science self-education, I picked up this book because descriptions made Williams sound a lot like Mary Roach, whose book I enjoyed. And this was much in the same vein, even with some of the same reservations.

It’s an eye-catching title, right? I quite enjoyed watching people’s reactions when I was reading this book at the pub, or when we had guests round and it was sat casually on the arm of the sofa. This book also started a fun game where for a week, Tim got to ask me every evening “What have you learned about breasts today?” and I was able to give genuine answers!

“We love breasts, yet we can’t quite take them seriously. We name them affectionately, but with a hint of insult. Breasts embarrass us…For such an enormously popular feature of the human race…it’s remarkable how little we actually know about their basic biology…Not even the experts among us are certain.”

I did learn some good facts, especially in the early chapters. This book starts strong, with a fun-fact-filled overview and then a plunge into what we know about breasts and evolution. Apparently there’s quite the division between scientists about whether breasts (and by that I mean human breasts, because we are the only animal to have breasts throughout adulthood, not just while lactating) evolved because men find them sexually attractive (and primarily mated with the women with breasts) or because it confers multiple advantages for feeding babies and for women’s health in general. Williams clearly leans toward the latter explanation and I was pretty thoroughly persuaded to her side.

“Modern life has…taken a strange and confounding toll on our breasts. For one thing, they are bigger than ever…We are sprouting them at younger and younger ages. We are filling them with saline and silicone and transplanted stem cells to change their shape. Most of us are not using them to nurture infants anymore, but when we do, our breast milk contains industrial additives.”

Williams shows a sense of humour but she doesn’t treat her subject lightly, for the most part. However, she does show her own bias a little too clearly. For instance, in the section on breast implants, she is clearly bemused by the whole idea and a little mocking. But at least some of the increase in implant surgery is down to the rise in breast cancer, which she devotes multiple chapters to later in the book. It seems to me that this subject merited a little more seriousness – perhaps a few more conversations with women about why they had the surgery.

“Double-D breasts on skinny women are not all that common in nature. (Barbie’s proportions are naturally found in one out of one hundred thousand women, according to researchers from the University of South Australia; Ken’s bod, by contrast, is found in one in fifty men.) Big, fake breasts have so thoroughly saturated mainstream entertainment and media that they’ve created a new standard by which boys judge girls and girls judge themselves.”

In fact, this was a bit of a running theme. For such a human subject, Williams failed to humanise the issues but instead tended to get clinical. I appreciated that there was plenty of real science explained very well, but I don’t think this is an entirely medical subject and yet Williams devotes more than half the book to what seem to be her pet topics – breast cancer and breast feeding. Yes, these are clearly important aspects of a book about breasts but I can think of plenty of areas left unexplored or only lightly touched upon. For instance, anthropology – what are the historical and geographical differences in social attitudes to breasts? (I would guess Williams shied away from this kind of discussion because it tends to centre around the sexual aspect of breasts, which she was distancing herself from.)

It’s not an overly clinical book. In fact, it is written engagingly and warmly. Williams happily uses herself and her pre-teen daughter as examples, from getting themselves tested for toxins before and after a sort of plastic detox (lots of chemicals used in lots of household plastics and flame retardants end up in breast milk, but only because our modern bodies are swimming in them) to detailing their family history of ages at child-bearing (which has a complicated relationship to chances of getting breast cancer). This adds a personal flavour while she also gives the stats and other wider details.

“In [macaque] society, daughters learn from hanging around their mothers longer and more often, and thinner milk means they stay close for more frequent feedings. The sons, by contrast, might be ‘tricked’ by the [relatively] fattier milk into feeling sated and therefore not feeding as often. It’s not a bad thing for the sons; they have more time to play and explore, skills they’ll need down the road when they leave the group.”

More than anything, this book owes a debt to Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (which I haven’t read and clearly really shoould), which Williams freely acknowledges. She worries about the effects of environmental toxins more than anything else and is fairly persuasive on this topic. She certainly made me glad I don’t live in the US! (Europe has much stronger regulations regarding chemicals, both on general sale and in household uses.) There is a bit of a US-centric angle, with plenty of specific studies from elsewhere but the general statistics are all US and almost always quoted without comparison. (There’s one place where she compares US stats with Canada and it’s a stark difference, which I found fascinating. Why? No suggestion is given, frustratingly.)

I preferred the opening chapters on evolution and puberty more than the later stuff but this was overall an interesting book on a subject we don’t tend to talk about, despite the importance of breasts in our lives. I strongly feel we need, as a society, to get over the sexualised view of women’s bodies and this book has a strong contribution to make to that.

Published 2012 by W W Norton.

Source: Borrowed from the library.

Challenges: This counts toward the 2014 Popular-Science Reading Challenge.