Anything is a weapon if you’re in deep enough trouble

Hawkeye Volume 1

by Matt Fraction

I think Tim is slowly but surely turning me into a Marvel fan. It began with the X-Men films, then the Avengers films, then the TV shows (Ultimate Spider-Man is really very good, and not just “for a cartoon”) and now finally he’s got me reading the comics. Although, thinking about it, I first heard the new Hawkeye comics recommended by Michael Kindness on the Books on the Nightstand podcast and passed that on to Tim, who read the first few and in turn told me I’d like them too. It’s all got a bit meta.

Anyway, the point is that I am writing this review as someone who has never read traditional superhero comics. I’ve read some of the alternative self-contained ones – Watchmen, Saga, League of Extraordinary Gentlemen – but never braved the whole mega universe of dozens or even hundreds of characters interacting over several decades that you are faced with when you pick up a mainstream Marvel or DC comic. Until now. I feel that I’m on the brink of a vortex of thousands of stories and I can’t decide if that’s daunting or exciting!

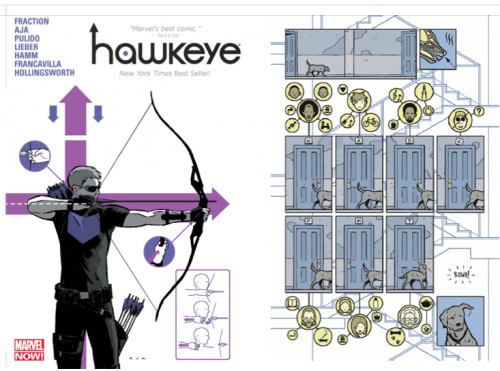

Of course, Hawkeye isn’t strictly a superhero. He’s a really really good archer. But he is part of the Marvel universe and interacts with proper job superheroes (Captain America, Iron Man, Hulk) and they all have their own storylines that weave in and out of each other’s. What’s nice about this latest series about Hawkeye is that its emphasis is on the time when Hawkeye isn’t working with the Avengers, so it can be read in isolation perhaps more easily and it has a look and feel that aren’t, to me, very “superhero”.

“You cowboy around with the Avengers some. Guys got, what? Armor. Magic. Super-powers. Super-strength. Shrink-dust. Grow-rays. Magic. Healing factors. I’m an orphan raised by carnies. Fighting with a stick and a string from the Paleolithic era. So when I say this looks ‘bad’? I promise you it feels worse.”

In fact, my initial attraction to these comics, and still one of my favourite aspects, is the extremely stylish design. The artwork is simple and stylised with a limited colour palette. This hardback volume includes one crossover comic from the series Young Avengers Presents and the difference in appearance really stands out. So I have nothing but praise for the whole art team.

But I think I wouldn’t have lasted 11 issues if the stories weren’t as good as the art. The basic thesis is that Hawkeye/Clint Barton is a good but flawed man with plenty of secrets and not the best history with women. He lives in New York City in an apartment building with a pretty varied bunch of ne’er-do-wells and tries to fend off the local branch of Russian mafia.

It’s not the first attempt to humanise a hero or to get under the skin of a man who’s afraid of commitment, but that doesn’t stop it from being an interesting combination with action adventure and daily life in a grimier corner of the city. There’s also the quite lovely relationship that Clint has with the Young Avengers Hawkeye, a teenager called Kate whose archery skills can match his but who needs advice on some other aspects of working seedy underworld jobs one day, and then for SHIELD the next day.

“Anything is a weapon if you’re in deep enough trouble. There’s no special training. No special skill. Just the belief that at any time you might have to hurt someone to stay alive. What kind of animal walks into a room and figures out what they can use to hurt people if they have to hurt? What kind…”

Another thing that makes this series stand out is the complicated timeline. It really isn’t always clear what order some events occur in. It’s certainly not linear, even within one issue. And some of the other information supplied can tend to the oblique, rather than spelling it all out for you. It’s genuinely complex writing that both draws you in and slows you down, which is good, as I’ve found that sometimes I tend to race through comics and almost skip the artwork. Here, so much is unsaid that I find myself “reading” the pictures carefully to find any clues not provided in words.

So was I won over because the first comic in this series is about Hawkeye meeting Pizza Dog? Possibly. I am a sucker for a dog lover. But I have stayed interested and am looking forward to volume 2 already. Yay, Hawkguy!

This collection published 2013 by Marvel.

Source: Excelsior! comic-book shop, Bristol.