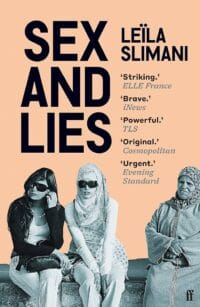

Book review: Sex and Lies by Leïla Slimani

I like essay collections but I tend to buy them at a faster rate than I read them. I fear they’re going to be less gripping than a novel or deal with serious subjects with less levity than fiction usually adds. Neither of which was a problem with Sex and Lies by Leïla Slimani (translated from French by Sophie Lewis).

I first heard about Slimani when her her novel Lullaby was published in English in 2018 and everyone was recommending it. I took one look at the synopsis and decided it was far too dark for me. That novel won Slimani the Prix Goncourt, making her the first Moroccan woman to do so. But it was actually her previous novel Adèle that triggered the conversations that led to Sex and Lies.

Adèle is about a woman living with sex addiction. When it came out in France, there was publicly expressed surprise that a Moroccan woman could have written on that topic, or indeed anything related to sex. Slimani didn’t set out to be shocking or controversial. She was after all following a centuries-old tradition of Arabic-authored literature that is frank about sex. But she acknowledges that in recent decades, things have changed on that front in her native country.

On her two-week Moroccan book tour for Adèle Slimani found that women and young people were keen to discuss sexual topics. But the conversations kept turning to the lack of freedom in modern Morocco. So she kept the conversations going, meeting people – mostly women – who were willing to be interviewed, albeit anonymously for the most part.

Of these 19 essays, 16 are structured around a conversation Slimani had with a Moroccan person about their relationship to sexual freedom. Slimani uses each of these conversations to explore a different nuance of sex in modern Morocco.

In Morocco it is illegal to have sex outside marriage; abortion is illegal; and women suffer the most in terms of social expectations and treatment by police. In particular, poor women bear the brunt as bribery is extremely common among those rich enough to evade arrest. And everyone pretty much denies the existence of LGBTQIA+ people – at least not in Morocco.

“Must I, like a large tranche of Morocco’s middle class, make do with a life of secrecy? Should I enjoy in my private sphere freedoms that are in fact prohibited by law?…For a long time, I bowed to the notion that to impose my views on others amounted to a kind of condescension. Now…I utterly reject the idea that identity, religion or any historic heritage should dispossess individuals of rights that are universal and inalienable.”

Essay topics include prostitution; the increasing conservatism of Morocco; the different expectations placed on men and women despite the law in theory being the same for both; and above all the reality of women’s sex lives in Morocco. Not graphically, but the fact they do have them.

Slimani takes particular aim at the idea that Islam inherently requires sexual conservatism. She points to ancient Islamic texts about sexual pleasure and the fact that some of Morocco’s most strict laws actually date from the colonial period and were written by French – non-Muslim – legislators.

“Moroccans swing between fantasy and vilification. We’re the fifth biggest consumer of internet porn in the world, yet at the same time we’re constantly calling for modesty…Sex is associated with the Other, the decadent West, while Moroccan and Muslim identity stands for virtue and modesty. But we’re forgetting everything. We’re forgetting that’s it’s we Arabs, we Muslims, who shocked the West with our erotic texts in the fifteenth century. We invented the realm of the erotic. And now we’re suffering from collective amnesia.”

What really stands out from this collection is that these Moroccan women are not happy with the current situation. And while I have no idea if these women are a representative cross-section, they do have quite varied lives and views. Even women who have willingly followed every rule are still frustrated. A widow is lonely and isolated because there is no way for her to socialise – she’s considered a potential threat to happy marriages if she mixes with couples, but there aren’t places for single women to socialise together. And even within marriage, if a woman has questions about sexual pleasure she has nowhere to safely ask those questions without judgement.

Slimani hopes to at least encourage conversations, encourage questions. What is mere inconvenience for many people, is real threat and humiliation for others. And she never forgets the gay people and adulterous women in Moroccan jails: “It’s the weakest, the poorest and the most marginalised that fate ultimately strikes.” But alongside the rise of Islamic fundamentalism she sees a rise in modernisation and openness that she believes will, painfully slowly, lead to sexual freedom.

Sexe et Mensonges: La Vie Sexuelle au Maroc published 2017 by Editions des Arenes.

This translation published 2020 by Faber & Faber.

One Comments

Comments are closed.