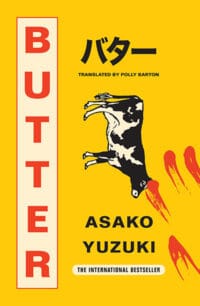

Book review: Butter by Asako Yuzuki

I don’t read all the books that get a tonne of hype, but I try not to be prejudiced against them either. If a blogger or bookseller I know shares my taste – or even better, a friend – recommends a book to me, I’ll give it a chance. And let’s face it, Butter by Asako Yuzuki (translated by Polly Barton) has been everywhere this year. But thanks to a friend recommending it, I get it. Because it’s really good. And even better, it contains a lot to talk about.

The narrative (mostly) follows Rika, a journalist at a prestigious weekly news magazine in Tokyo. Unmarried in her mid-30s, she is at once judged and admired for being a careerwoman – not an easy thing to be in Japan, we’re told. She’s the only woman in her department and works long hours, often seven days a week. She lives on junk food and sees her sort-of boyfriend Makoto only occasionally – usually when he is out drinking late and needs a nearby bed to sleep in.

Her best friend is Reiko, in some ways Rika’s opposite. Reiko is married, cooks every night and has quit her job in PR while she tries to get pregnant. She’s also full of curiosity and (genuinely) helpful advice for her friend.

With the prospect of a promotion on the horizon, Rika needs a big story and she might now have it. Convicted serial murderer Manako Kajii is awaiting retrial at Tokyo Detention House. She would date rich men, cook gourmet food for them, lived a lavish lifestyle thanks to them, and then one by one they died in mysterious circumstances. It was a huge sensational case, in part because Kajii was already Internet famous, with a popular blog about food and cooking.

Kajii has never given an interview to the press, but Rika thinks she can be persuaded by someone open to the possibility of her innocence. Rika is certain that all the press around Kajii’s original trial was steeped in misogyny and fat-shaming, which may have influenced the jury.

Their first few meetings are fractious. Rika is initially repulsed by Kajii’s appearance, her lack of embarrassment about living for pleasure, and her hatred for all other women. Kajii is in some ways deeply old fashioned. She believes women’s role in life is to please men and she hates feminists. All life’s ills, in her eyes, have their roots in women who didn’t sufficiently look after their men. Women should dress, wear their hair and make up, cook and clean all how their men want.

But from the start there are contradictions, because Kajii also declares she lives for her own pleasure. She worked as a “professional girlfriend” because she loves sex and loves good food. Rika struggles to empathise with her subject, but is so fascinated by her that she doesn’t spot the inconsistencies.

To better understand Kajii, Rika begins to cook recipes from her blog. This is where Yuzuki truly excels. The food descriptions are so mouth-watering and yet never took me out of the story. Rika is discovering the pleasure of eating from the basics first. She starts with steamed rice topped with butter and soy sauce. A simple recipe almost impossible to mess up (especially if you own a rice cooker). There’s just one problem: Japan is in the grip of a butter shortage. All dairy, but especially butter, is near impossible to get hold of. Following a tip from Kajii she tracks down a single package of imported European butter. It’s extremely expensive but Rika is immediately won over.

“The first thing Rika felt was a strange breeze emanating from the back of her throat. The cold butter first met the roof of her mouth with a chilly sensation, contrasting with the steaming rice in both texture and temperature. The cool butter clashed against her teeth, and she felt its soft texture right down into their roots. Soon enough, just as Kajii had said, the melted butter began to surge through the individual grains of rice. It was a taste that could only be described as golden.”

Rika’s friends and colleagues soon become concerned about her, for two very different reasons. She’s gaining weight, an amount that is commented on so often it seems it must be a large amount until Rika gives her actual weight at one point. She is still small by Western standards. Japan’s beauty standard for women is extreme, and women are judged harshly if they don’t conform.

The other concern is that Rika has become mesmerised by Kajii. And this one might be legitimate, in that Kajii is clearly a skilled manipulator. But their odd relationship has opened Rika’s mind to the option of not conforming to society’s expectations.

The story does go to some strange places, and it can be hard to take it all literally. But with Japanese literature I don’t think we’re supposed to. Sometimes a subplot that seems surreal and placed there only to underline a metaphor is just that. And that’s just part of being an indirect language. (Thank you to Sara and Cariad’s Weirdos Book Club for helping me to that insight.)

What I liked most about Butter – possibly aside from the incredible food descriptions – is Rika’s voyage of self-discovery. At the novel’s start she only really has one person in her life: Reiko. She barely sees her mother or boyfriend. She doesn’t open up to her colleagues and keeps her older trusted news source Shinoi at arms length. But as she learns to enjoy, and cook, food, she also learns to open herself up to people. She creates a found family, something I’ve never seen in a Japanese context before.

And the food! Even when it’s a meat dish I was salivating. I am such a sucker for food telling a story. Polly Barton’s translation is excellent, giving just enough context without flattening the specific Japanese food and places.

Yuzuki comments a lot on gender and appearance. Hers is absolutely a feminist perspective, saying the rest of the world shouldn’t dictate what you look like, you can judge what is healthy and right for you. And I agree with that wholeheartedly. Then there are repeated references to Rika having been a “prince” at her all-girls high school (where she met Reiko) – a late bloomer who looked masculine and became the object of many girls’ crushes. Nothing wrong with that, and Rika doesn’t seem to have objected, but it did feel at times dangerously close to queerbaiting. Rika and Reiko sometimes have a co-dependency and need for each other that felt like it might be more than friendship.

“With deliberate roughness of touch, Rika rubbed a thick coat of Nivea cream into her bare skin. She removed her contact lenses and replaced them with glasses, and pulled back her hair tightly with an elastic band. She needed to get rid of all traces of softness and sweetness about her before joining the man she was about to meet. The sight of the person in the mirror before her, tall and wiry and of indeterminate gender, gave her a sense of deep satisfaction.”

It’s worth saying that this is probably not a book to read if you have any form of food or eating disorder, or shame around body image. There is so much food in it. And equally as much discussion of weight gain and loss. And oh dear, the fatphobia. I do truly believe that those are the opinions of specific characters, and Yuzuki’s message is an anti-fatphobic one, but I can see that this would still be a tough read if that’s a sensitive subject.

One final caveat. I both started and ended this book loving it. But I found a fair chunk of the first half on the stodgy side. Rika’s initial lack of interest in food, paired with Kajii’s manipulative hatred of other women, makes neither of them a comfortable target for empathy. And Reiko is equally complex: a capable, smart woman who has lied to everyone in her life. I like this complexity, but it did make an already long book a very slow read for me.

First published 2017 by Shinchosa Publishing.

English translation published 2024 by 4th Estate.

Source: Borrowed from a friend.

She doesn’t have a brother

There was definitely mention of a brother and sister-in-law early in the book, but perhaps they are Reiko’s relatives not Rika’s. I spent a month reading this so my memory of the first third or so is a little hazy.