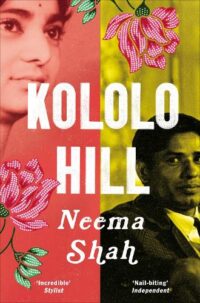

Book review: Kololo Hill by Neema Shah

Back in March, I bought two copies of Kololo Hill in an auction to raise funds for British-Ukrainian Aid. The author, Neema Shah, kindly offered to sign the books with personalized recommendations and I thought here was a great opportunity to do a readalong with my friend H, who I was planning to see soon. Cue months of Covid- and non-Covid-related reasons for us delaying our get-together until in August I finally posted H’s copy of the book to her. In September we agreed to start reading the book. In October I finally read it.

Back in March, I bought two copies of Kololo Hill in an auction to raise funds for British-Ukrainian Aid. The author, Neema Shah, kindly offered to sign the books with personalized recommendations and I thought here was a great opportunity to do a readalong with my friend H, who I was planning to see soon. Cue months of Covid- and non-Covid-related reasons for us delaying our get-together until in August I finally posted H’s copy of the book to her. In September we agreed to start reading the book. In October I finally read it.

It’s a good book; don’t judge it harshly for my delay.

It’s 1972 and Asha and Pran are newly married. They live in the leafy Kololo Hill suburb of Kampala with Pran’s parents, Jaya and Motichand, and his brother Vijay. Pran is planning to expand his shop; Asha is settling in with her in-laws. But in the background of their life is Uganda’s increasing anti-Asian violence, the curfew imposed on them, and the sounds of gunfire at night. Slowly that background becomes foreground, becomes almost all their lives revolve around. And then Idi Amin issues an edict that all Asians must leave Uganda within 90 days. It’s not much time for them to make the necessary plans.

Thanks to the legacy of colonialism (which is the reason many Asians came to Uganda in the first place), the family have a mix of British, Indian and Ugandan passports. Neither Britain nor India will take all of them, so they must leave separately. There’s also a question mark hanging over the fate of their house servant December, who is Acholi – one of the Ugandan ethnic groups being persecuted by Amin. Unlike his employers, December has nowhere to run to, so his choice is between hiding where he is or risking being smuggled out of the country.

“She’d picked up everything she knew about [December’s family] in snippets, a life compiled by patchwork. He didn’t talk about his family often. Jaya recalled a time, a year or so after she had arrived in Uganda, back when both of them could still run fast across the yard when it rained and when they both had luxurious heads of thick, dark hair. He’d come to the house one morning beaming as he clutched a box of mandazi…to celebrate the birth of his daughter, Aber…Jaya asked him to bring Aber to the house one day…but they’d never had the chance.”

Shah includes the context for the expulsion, so we can see the spurious grounds Amin’s government based their dislike of Asians on. After thousands of mostly Indian men were brought to Kenya and Uganda by the British to build railways and other infrastructure, many stayed and created successful new lives in these East African colonies. They created their own wealthy Asian neighbourhoods, such as Kololo Hill, and tended to socialise and marry among their own. Much of the money they earned was sent to relatives in India or Britain.

It’s easy to see how resentment might begin to simmer after the British left in 1962 and the Asians stayed on. But for people like Asha and Pran, Uganda is their country too, their birthplace, the only home they have ever known. India is a foreign country their parents sometimes spoke of but they have never visited. Even among their parents’ generation, Jaya talks to a friend who has been back to India to visit family and felt like a tourist there, mocked for her old-fashioned Gujarati. Jaya herself is aware that she speaks softly and subserviently in Gujarati, the way she was raised, but in Swahili she can be assertive and emphatic, the person she prefers to be.

The novel is split roughly in two: part one in Uganda, part two in England. The first half is the story of ordinary, comfortable lives gradually disintegrating into something close to a warzone. A middle-class, business-owning family forced to leave everything behind except a small bag of clothes and keepsakes each. The second half of the story is about survival in a strange, new place. The three family members who initially fly to the UK are British passport holders. They have every right to be where they are. But they have no money and don’t all speak English, so they are beholden to the system.

“In Uganda, the rain was like a brief lovers’ tiff: quick and swiftly forgotten, soaked up by the sun’s rays in no time. English rain, on the other hand, lingered long after it had fallen, sulking on the pavement for hours on end.”

As I get older I increasingly find that the moments in books and films that make me cry aren’t the deaths, or even the grief following those deaths, but rather the small moments of kindness. In this novel, after Asha and family have feared for their lives for months, on arrival in the UK they’re greeted by St John’s Ambulance volunteers who give them winter coats. I cried so much at that.

But it’s not all rosy from there, of course. As they struggle for jobs, a secure roof over their heads and to reunite their family, a question looms over them. Do they want to stay in the UK? Is the life they are building here temporary or permanent?

In among all this upheaval, Shah doesn’t let her readers forget that these characters are human beings who already had hopes, dreams, rivalries and disagreements. Asha and Pran were still newlyweds, just getting to know each other, as their lives turned upside down. It’s a lot of stress for any relationship, and the decisions they make in the heat of the moment can suddenly have life-changing consequences that may change how they feel about each other.

I really enjoyed this book. I grew to love Asha and could happily have read another 200 pages of her story. That said, I think Shah chose the perfect ending, with just the right combination of questions answered and left open.

First published 2021 by Picador.

One Comments

Comments are closed.