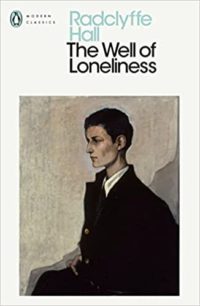

Book review: The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall

I had been intending to read The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall for years and I recently spent a few months making slow progress through this classic of lesbian fiction. As it’s Pride Month, this seemed like a good book to pick out from my read pile to write a longer review. First published in 1928, this is both very much of its time (in style) while being very ahead of its time (in content).

I had been intending to read The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall for years and I recently spent a few months making slow progress through this classic of lesbian fiction. As it’s Pride Month, this seemed like a good book to pick out from my read pile to write a longer review. First published in 1928, this is both very much of its time (in style) while being very ahead of its time (in content).

It’s the story of Stephen Gordon, a woman raised in all the comforts of a large country estate, the only child of a doting father who teaches her to ride, hunt, study and fence. It’s a life of privilege and would not be out of place in a Jane Austen novel, except for the repeated reservations of Stephen’s mother and neighbours about raising a girl quite so much like a boy.

When it gradually becomes clear in her teens and early 20s that Stephen is attracted to women, her father and her tutor Puddle understand before she does and try to protect her, while her mother is disgusted. The rest of her life follows a similar pattern of finding people who accept her and people who hate her.

“Outrageous, Puddle would feel it to be, that wilfully selfish tyranny of silence evolved by a crafty old ostrich of a world for its own wellbeing and comfort. The world hid its head in the sands of convention, so that seeing nothing it might avoid Truth. It said to itself ‘If seeing’s believing, then I don’t want to see – if silence is golden, it is also, in this case, very expedient.’ ”

Stephen’s wealth gives her a safety net that prevents the prejudice she faces from ever leaving her destitute or in any real fear of becoming so. I must admit that I had expected a book billed as a tragedy to go to darker places earlier on. And though Stephen certainly does suffer from homophobia and misogyny, as well as loneliness and misunderstanding, the cushion of wealth and being from a “good family” prevented me from feeling as much sympathy as I might have.

Like many books of its era, the language feels a bit stilted and old-fashioned now. But I can see why many people still laud this book, and how revolutionary it must have been, speaking frankly about Stephen’s relationships and those of her gay friends, and pointing out the hypocrisy and unfairness in how they are treated. It has a lot to say about women’s abilities being limited by what society allows.

I found this a slow read overall. While it reads a bit like a George Eliot novel in style, it lacks Eliot’s elegance. It relies instead on plot, and the plot takes a while to get going. But it does depict women’s roles in the First World War and the LGBTQ community in Paris in the 1920s, both of which are fascinating subjects. I was particularly interested in the manner in which the war enables Stephen to find her community, in a roundabout way, as gay women found each other through volunteering for the war effort.

“There was many another exactly like her in this very city, in every city; and they did not all live out crucified lives, denying their bodies, stultifying their brains, becoming the victims of their own frustrations. On the contrary, they lived natural lives – lives that to them were perfectly natural. They had their passions like everyone else, and why not?”

Hall repeatedly, frequently uses the word “queer”. She never directly uses it in the sense of meaning LGBTQ, but she does describe Stephen’s character or behaviour as queer too often for it to be coincidental. According to the 1937 Concise New Partridge Dictionary of Slang, use of the word queer to mean gay was, from around 1914, “derogatory from the outside, not from within”. So arguably this book was an early attempt to claim the term for the gay community, to acknowledge its meaning of “different, but not bad”.

That said, some of Hall’s language about gay characters is derogatory even for its time. Stephen is weirdly judgmental about effeminate characteristics in male friends considering that she could be read as a trans man rather than a lesbian. As a child, Stephen outright states “I’m a boy” and as an adult frequently wishes she were a man. She’s also biphobic, and repeatedly calls herself an “invert”, which feels a little self-hating.

“Nature was trying to do her bit; inverts were being born in increasing numbers, and after a while their numbers would tell, even with the fools who still ignored Nature. They must just bide their time – recognition was coming. But meanwhile they should all cultivate more pride, should learn to be proud of their isolation.”

It’s a strange combination of call-to-arms for gay pride, and depiction of lesbianism as a lonely life that’s somehow both dull and full of trials. I’m glad to have read it for its historical significance, but I couldn’t honestly call it great literature.

Published 1928 by Jonathan Cape.

Source: Project Gutenberg.