It was the climax of the accumulated impressions

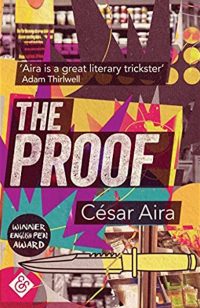

The Proof

The Proof

by César Aira

translated by Nick Caistor

I didn’t exactly love this book, but the second I finished it, I felt an urge to write about it. And that doesn’t happen so often lately (as you might have guessed from the declining frequency of reviews on this website). So it clearly had an effect on me.

This slim novella manages to be both thoughtfully philosophical and explosive with action – it just does one then the other. There is a sense of menace from the start, when 16-year-old schoolgirl Marcia is out for a walk in Buenos Aires and realises that as it is starting to get dark, big groups of young people are beginning to gather outside cafes and record shops. Out of the blue she is propositioned “Wannafuck?” – which is actually the first word of the story.

The shout has come from two girls around Marcia’s age who are dressed as punks (the novel was written in 1989) and follow her as she tries to hurry away and ignore them. When that tack doesn’t work, she strikes up a conversation and finds herself both appalled and fascinated by their crude antagonism. The girls – who call themselves Mao and Lenin – agree to go with Marcia to a cafe to talk and this is where the bulk of the story takes place.

“The music changed her mood, took her to its silent conclusion. As this had not happened with the music from the two earlier record shops, it must have been down to how good it was, though possibly it was the climax of the accumulated impressions. The music was the remaining resistance needed to make the mall completely fluid.”

This is a fast read, pacier than you might expect for something that not only dwells on philosophy but also describes minute details. I don’t know if this was the original or the translation, but I found some of the painstaking description a little tedious. Though later in the story some of those details begin to have a purpose.

Marcia holds something like admiration for the punk girls, even though it’s clear to the reader that she has far more interesting, nuanced thoughts than they do. Mao and Lenin exude an air of great purpose, but in truth they are just angry young people looking for an outlet for their violent thoughts.

Of course, their anger could itself have a complex and fascinating origin, but Aira doesn’t give us that. The story he is telling is that of a very ordinary, educated, middle-of-the-road young person being intoxicated by the chance to ally herself to people outside social norms. And how Marcia reacts to Mao and Lenin’s increasingly antisocial behaviour is both confusing and completely believable.

“[This] was said in a paroxysm of violence that revealed a new dimension to the punks…They faced each other like two powerful beasts, both of them sure of their own strength, and even of the balance of power between them, at an excessive level.”

It’s hard to explain why without spoilers, but while reading the second half of this book I was frustrated by the pace and the characters, and not wholly enjoying it. But then on reaching the end I found myself reassessing what I had read, seeing how carefully the narrative builds to its conclusion. I probably won’t but I could completely understand if some readers finish this book and immediately reread it.

La Prueba originally published 1992 by Grupo Editor Latinoamericano.

This translation published 2017 by And Other Stories.

Source: I subscribe to the publisher.