Our father refused to compromise, and live a life of silence in the face of oppression

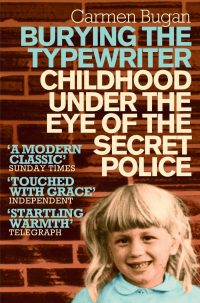

Burying the Typewriter: Childhood Under the Eye of the Secret Police

Burying the Typewriter: Childhood Under the Eye of the Secret Police

by Carmen Bugan

This is my Romania selection for the EU Reading Challenge, and it’s so far my only book in this challenge that was originally written in English. I remember adding this to my wishlist when it was first published. Past me was smart.

It’s a memoir of the author’s first 18 years, when she lived in Romania. She and her family left Romania in late 1989 under threat of death and this is Bugan’s story of how they reached that point. It’s very much told from her own point of view, as the oldest child of Ion Bugan, who was twice imprisoned for protesting Nicolae Ceaușescu’s regime.

The book opens with Carmen’s early childhood, which was idyllically happy. Though her father was an activist long before his marriage and her birth, and never stopped secretly protesting, she was oblivious for many years. As the 1970s turn into the 1980s, the warning signs appear (with of course decades of hindsight). When Carmen turns 11 she begins to pay attention to the radio programmes her parents listen to; to the food shortages and fights over rationing on the streets; to the arguments her parents have about moving near to the border and becoming self-sufficient.

“At school we repeat mechanically the Communist Manifesto but it does not represent the kind of struggle I find at my parents’ shop. Here we are all the same class and we struggle against each other: for basic food. At the of 11 I can see this, but not speak about it, and this is yet another sort of knowledge.”

It’s through one of the radio shows that she learns about her father’s first arrest. A priest, speaking from America, recalls the horrors of being held in a Romanian prison in the 1960s, and the young man he shared a cell with, a young activist who nearly died. Ion’s tears lead to a confession that he was that young man, it was his life the priest saved.

Shortly after this, Carmen’s parents start burying the typewriter of the title. When they bought it, they trained Carmen and her sister Loredana to tell anyone who asks that they only use the typewriter to type up recipes and poems. The girls hear the keys tapping away late into the nights, then the typewriter is buried in the garden before daylight. They have their suspicions about what’s going on, but it’s years before the truth is confirmed.

Then one day, while her sister is away at gymnastics school and her mother and baby brother are in hospital, Ion loads up the car with banners and pamphlets and drives away. He doesn’t come home. That day, the Bugans’ home is overrun by secret police, who strip the house of food, valuables and documents then seal all the doors. Carmen and her grandmother are questioned for days without being allowed to change their clothes or eat. The police refuse to tell Carmen where her father is, whether he’s alive. Over the following years, they stake out the house, letting themselves in daily to question the family. They follow Carmen to school and plant microphones around the house.

The contrast between the innocence of childhood and the reality after Ion’s arrest is stark. But Carmen was still insulated to some extent from the truth. The full horrors of what happened to Ion are never given in full, because this is the story of those left behind, but we do learn some of the details.

“No matter how hard we study…Loredana and I are earning low marks and lots of abuse from the teachers…The Securitate tells us at home that we are poor students, that we make bad pioneers…The other children are encouraged to taunt us and in the playground they throw stones at me calling me ‘daughter of criminal’…Loredana and I are trapped, and our isolation is made more painful because our father refused to compromise, and live a life of silence in the face of oppression.”

The trigger for this book was that some of the secret military documents about Ion Bugan’s case were made available to his family in 2010 and 2011. Scans of some of these files are included at the start and end of the book, including the reveal of who was in charge of the investigation. Carmen says in her afterword that she had written the majority of the book before learning that particular detail and she’s glad, because she would have written the whole thing differently otherwise.

It’s an amazing story, sobering in how quickly awfulness can become everyday – whether that’s queueing for scraps of bread or having police patrol your garden at night. Carmen the child is ambivalent about whether she thinks her father did the right thing – she’s proud of him for standing up for his fellow man but also hates him for putting their family through years of hell to make his point.

For all the horrors depicted, this is a quick and often heartwarming read. Carmen is a poet and it shows in her turns of phrase.

Published 2012 by Picador.

Source: Waterstones.

By great good fortune, Carmen and I lived in the same village in France for a couple of years and she has become a dear friend. I admire her writing very much, including her poetry, and she’s a great writng instructor, as we all found out at the Geneva Writers’ Group.

Oh that’s amazing, I can definitely imagine her as a great writing instructor.