Gladly will I oppose my body to his

The Mabinogion

Translated from Middle Welsh by Lady Charlotte Guest

This was the first book I started for the EU Reading Challenge, but ended up being the 10th book I completed. Perhaps I should have searched out a more modern translation when I first started to struggle. These are ancient tales, widely considered the oldest surviving British literature in prose form. They were almost certainly oral tales for a century or more before their earliest known recording in 1350–1410. Lady Charlotte Guest translated the tales into both modern Welsh and English in the late 19th century. Which I thought made them an interesting inclusion on my EU list.

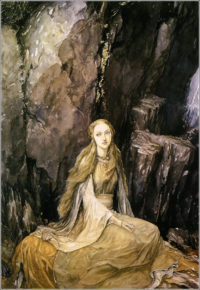

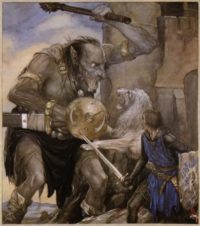

The 11 stories in this volume have different authors, all unknown, and in fact only the first four are strictly the Mabinogi. The rest are medieval romances; some early Arthurian knight tales; and the tale of Taliesin the bard. My particular edition of The Mabinogion includes full-page illustrations by Alan Lee, who is now better known for his Lord of the Rings illustrations. It is a beautiful object.

There is a bit of a theme in these tales of women with magical powers, many of whom have pretty awful fates. For instance, the first of the Mabinogi is “Pwyll, Prince of Dyfed” and tells the story of Pwyll’s attempts to romance Rhiannon, an Otherworld woman who runs rings around him rhetorically and literally (she’s pretty awesome), but eventually falls in love with Pwyll and marries him. However, when their son Pryderi disappears on the night of his birth, she is accused of matricide and imprisoned.

The story has a happy ending, but not before Rhiannon has spent years in prison. And she’s not the only wrongfully treated woman here. I can’t decide if this is fear of magic and witchcraft, or misogyny, or both. There’s plenty of magic, used for good and evil, but even when used for good it does tend to end badly.

Rhiannon and Pryderi reappear in the third of the Mabinogi, “Manawydan, the son of Llŷr”. In this tale, Pryderi (now king of Dyfed) and his bestie Manawydan (rightful king of Britain) travel to England but keep having to move on because in each town or village they are resented for their superior skills in whichever trade they have taken up. It’s a funny (and completely understandable) comment on the relationship between England and Wales. The rest of the tale takes place in Dyfed where a series of enchantments over the region must be overcome.

The stories themselves are fascinating pieces of folklore, including characters and elements familiar from later texts. Tolkien (naturally) borrowed from The Mabinogion in his own world-building. And The Mabinogion’s Bran the Blessed must have been an influence on George R R Martin, seeing as he’s a one-eyed king whose name means crow or raven.

I must admit that this translation is a bit plodding and dry, and super old-fashioned. I’d love to see a translation that’s more modern and/or by an author I enjoy the style of. This problem became more pronounced for me in the later stories where magic is phased out and Christianity a prominent theme. But I did enjoy/get distracted by my own lame attempts to pronounce all the Welsh names as I read them.

“ ‘Verily,’ said the messengers, ‘Pryderi saith that it were more fair that the man who did him this wrong should oppose his own body to his, and let his people remain unscathed.’ ‘I declare to Heaven, I will not ask the men of Gwynedd to fight because of me. If I am allowed to fight Pryderi myself, gladly will I oppose my body to his.’ And this answer they took back to Pryderi.”

As a childhood fan of all things Arthurian, it was interesting to read tales referring to King Arthur and his knights that have survived from the 14th century, but are understood to be much older, predating not only Le Morte d’Arthur by Sir Thomas Mallory (1485) but possibly also Chrétien de Troyes’ Arthurian tales (12th century). These certainly aren’t the oldest recorded mentions of King Arthur but there is a possibility that the oral tradition they came from is, seeing how rooted he is in Welsh and Breton mythology. So it’s fascinating from a scholarly standpoint to read these, even if I do wish they were more engaging as prose. And if you are interested from a scholarly standpoint, my HarperCollins edition includes Guest’s extensive notes (116 pages of them).

If you know of a better translation of The Mabinogion, do let me know, as I’d love to try it.

This translation first published 1838–1845.

This illustrated edition first published 1982.

Source: I’m pretty sure I bought this as a teenager during my Arthurian obsession. So it will have come from an actual real-life bookshop, but I don’t know which one. Possibly the long-gone Ottaker’s in Gloucester, or my 16th birthday trip to Hay-on-Wye, or maybe my favourite bookshop of them all, the Forest Bookshop (RIP).