I think that’s a reasonable amount of time to feel hopeless about everything

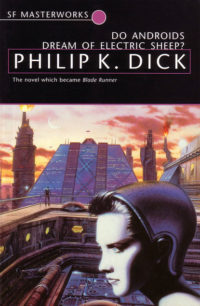

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

by Philip K Dick

I had been meaning to read this book for years. I love the film Blade Runner and I have loved the other books by Dick that I’ve read. What finally made me pick this up wasn’t last year’s Blade Runner 2049 but a combination of the new Electric Dreams TV series based on Dick’s short stories, and an interview with Janelle Monáe on BBC 6Music (yes, the obsession continues).

If, like me, you know the film but not the book, then this is both familiar territory and bursting with new things not in the film. It opens with Rick Deckard and his wife Iran discussing their mood organs – devices on which they can dial up a specific emotion, from rage to a businesslike attitude to “awareness of the manifold possibilities open to me in the future” – and their electric sheep. Deckard is obsessed with owning a real-live animal and hates that their animal is a fake.

“I realized how unhealthy it was, sensing the absence of life, not just in this building but everywhere, and not reacting – do you see? I guess you don’t. But that used to be considered a sign of mental illness; they called it ‘absence of appropriate effect’. So I left the TV sound off and I sat down at my mood organ and I experimented. And I finally found a setting for despair…So I put it on my schedule for twice a month; I think that’s a reasonable amount of time to feel hopeless about everything, about staying here on Earth after everybody who’s smart has emigrated, don’t you think?”

This is a post-apocalyptic San Francisco where the dust clouds block out the sun. Most animals have become extinct and most humans have moved to the off-world colonies. In the colonies, androids are used as slave labour. Sometimes androids escape back to Earth and it is Deckard’s job to “retire” – kill – those that come to his corner of California. The difficulty with this is that the newest line of androids – the Nexus 6 – are so human-like that it takes a time-consuming test to identify them – the Voight-Kampff test.

Like the film, this book deals with the complex issues surrounding artificial intelligence. There are many about-turns on whether Deckard, or many other characters, is in fact android. Can an android desire a real-life animal the way he does? Can an android feel empathy? Can, or should, humans feel empathy for androids? And if empathy is the only discernable difference between humans and androids, what about humans who have trouble with empathy?

“Too old to emigrate, Hannibal Sloat, although not a special, was doomed to creep out his remaining life on Earth. The dust, over the years, had eroded him; it had left his features grey, his thoughts grey; it had shrunk him and made his legs spindly and his gait unsteady. He saw the world through glasses literally dense with dust. For some reason Sloat never cleaned his glasses. It was as if he had given up; he had accepted the radioactive dust and it had begun its job, long ago, of burying him. Already it obscured his sight. In the few years he had remaining it would corrupt his other senses until at last only his bird-screech voice would remain, and then that would expire, too.”

This book is an exciting, fast-paced thriller. But like all science fiction, it’s also a means of exploring issues important to its author. There’s the obvious analogy to slavery, with the androids that Deckard kills being escaped slaves. But the androids also invite the question of what it means to be human. Dick teases us with which emotions they experience, as they spend so much of the book trying to pass as human. And as Janelle Monáe’s entire career demonstrates, androids can also represent any “others” in society.

Dick follows this angle with the character of J R Isidore, one of the people whose health has been affected by the radioactive dust to the point that he was turned down for the colonies. He appears to have difficulty with learning and with social interactions. Not only is he doomed to live in a deserted suburb, scraping a living, he is also treated abominably by everyone he comes into contact with. He is called names ranging from “special” to “chickenhead”. In an early scene it is suggested that “specials” would not pass the Voight-Kampff test. Are they therefore less than human as far as this society is concerned? Or are the androids more human than this society wants to admit? Isidore is also notable in that he is the only character not prejudiced against androids, but it is unclear if this makes him open-minded or gullible.

** Spoiler warning **

I can’t finish up this review without mentioning something that I went into the book worried about. There is one scene in the film that has always bothered me – the sex scene between Deckard and the android Rachael that’s basically rape. An equivalent scene does exist in the book and the sex is thankfully consensual, but Rachael is described as having no visual emotional response to being kissed and it made me wonder if that’s what the film was going for (though if it was they fell far wide of the mark).

The book has a related but different problem. The very few women in this novel are all sexually manipulative femme fatales. Except Deckard’s wife, who appears largely asexual, with a tendency to depression. She feels things deeply. She is also the only human woman in the book. So are Dick’s Raymond Chandler -esque descriptions of the female androids pure misogyny, or are they a comment on the kind of society that creates artificial slave women, or even a reflection of the attitude of Deckard himself, who is far from heroic?

** End spoiler **

This is a really enjoyable read, even more so than the other Dick books I’ve read. Perhaps because it’s using the tropes of a trashy detective novel.

First published 1968 by Doubleday.

Source: Borrowed from Tim.