She succeeds in doing what no one ever dared think she would

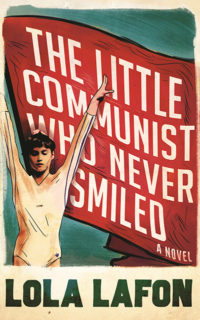

The Little Communist Who Never Smiled: a Novel

The Little Communist Who Never Smiled: a Novel

by Lola Lafon

translated from French by Nick Caistor

Like many who dabbled with gymnastics in their youth, I have a small obsession with former Romanian gymnast Nadia Comăneci. I remember a year or two when a VHS copy of the made-for-TV biopic Nadia was passed around my gym club like a precious jewel. I watched it several times during the week I took it home. Years later I realised that this was the same Nadia on our TV screens during every Olympics and World Championships, only now she was an American coach. But despite my love for Nadia the gymnast, I never really looked further into her life.

On reflection, it should have been obvious that her life was more interesting than the bare facts of her gymnastic achievements. Born in 1961, the Romania she was raised in and trained in was a “Marxist-Leninist one-party state”, as Wikipedia puts it, until the 1989 revolution that ousted – and executed – the state’s controversial leader Nicolae Ceaușescu. Nadia defected to the US just weeks before the revolution.

As the subtitle and author’s note make clear, this is fiction, but it’s fiction written in a journalistic style. Lafon uses real sources – articles, footage, interviews, even Nadia’s own memoir – and an imagined dialogue with Nadia to piece together her life from the age of 7, when she was picked for training by legendary gymnastics coach Bela Karolyi, to 1990, a year after her mysterious escape. As such this reads like a particularly well-written biography, careful in most places not to invent what cannot be verified and to be clear where events are disputed. But there is, of course, invention – not least those conversations with a current-day “Nadia C”.

“He sprinkles the choreography with acrobatic skills that as yet have no name, invents what he dreams for her at the same time as he instructs her on the movements he requires; she succeeds in doing what no one ever dared think she would accept…Her knees fill with liquid as a reaction to all the repeated shocks, her joints are covered with patches of hard skin. They have to be careful that the open blisters on her hands don’t get infected by dust from the floor or the chalk. Her body–weight ratio is so perfect that when she runs to leap into backward tumbles you can’t quite believe her feet are even touching the ground.”

This style, with the invented journalist conversations interrupting the narrative in most chapters, took a little getting used to. But they added necessary perspective, allowing the story to reflect both inside and outside views of communist Romania, and of Karolyi’s famously strict training methods.

Lafon’s prose is lyrical, ethereal, which perfectly matches the danger-defying acrobatics so prominent in the early pages, but means later on there are some troubling facts that feel a little obscured, that took me some time to piece together – primarily around Nadia’s relationship with her body. This is an ongoing theme: is it her body or Romania’s or gymnastics’?

It’s all tied up in the fact that her initial success came when she was so young – European champion at 13, Olympic champion at 14 – and a lot of her appeal was her tomboyish, childlike innocence. So when two years later she started to develop curves (and got her period), a lot of people were affronted. She had hugely popularised women’s gymnastics but the backlash was a Hello! magazine-style dissection of her every public appearance throughout the world.

Lafon’s background gives her the ideal dual perspective on Nadia’s story. She was born in France but spent much of her childhood in Bucharest, before moving back to France as an adult. Her media references therefore come from France and occasionally its neighbours as well as the more familiar US and UK sources.

The details of the communist regime, and in particular Ceaușescu’s leadership, are largely saved for the second half. Early on we see young Nadia and her team-mates bewildered by the capitalist displays in the West, the girls laughing at TV adverts and begging their coaches to be allowed to take free badges, key-rings and teddy bears from the sponsors’ stalls. But this is contrasted with Nadia telling a story of the first time her mother visited her in the US and broke down in tears in the local supermarket:

“I try to understand. Was Stefania crying tears of joy faced with the emotion of all these new choices? But Nadia interrupts me almost brutally. She was disgusted at the absurd piles of stuff, she corrects me. Sad at feeling herself tempted by desire on seeing all these heaps of nothing. ‘Back home there was nothing to desire. But in the West, you are called on to desire constantly.’”

Certainly Lafon’s Nadia has little negative to say about her experience of Romania. So then why leave, particularly in the arduous and dangerous manner in which she did? Lafon gives plenty of possible reasons, both personal to Nadia and more general. And it’s hard to fault Nadia’s logic when she credits communism with her success. She was from a small town, giving a few hours a week to gymnastics as a hobby. Then along came Bela and Marta Karolyi to her little town, with their painstakingly researched training and diet regimes, ready to throw all of the state’s resources at the little girls who would give them all in return. After the first few years Nadia chose to move into the new gymnastics school full-time despite living a short walk away, because those minutes could be better spent in training.

Dedication and fearlessness were in Nadia’s nature, which made her the perfect student for the Karolyis. But, in Lafon’s telling at least, she also took to heart every negative comment and therefore spent years blaming herself for her adult body. The story gets pretty dark, and isn’t really suitable for the age at which I first discovered Nadia. But I think if it had been made appropriate for a younger audience a lot of the detail and nuance would have been lost.

After an uncertain start, I ended up loving this book, and having a new appreciation for Nadia the adult, who faced huge difficulties and came through them smiling, unlike the child of the book’s title.

La Petite Communiste qui ne souriait jamais published 2014 by Actes Sud.

This translation published June 2016 by Serpent’s Tail, an imprint of Profile Books.

Source: A copy was kindly supplied to me by the publisher in return for an honest review.