Leaving a vacuum in the air where his voice had been

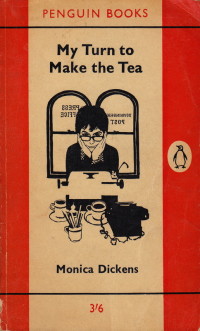

My Turn to Make the Tea

My Turn to Make the Tea

by Monica Dickens

I have been looking forward to reading my beautiful if slightly fragile copy of the 1962 Penguin reprint of Dickens’ memoir of her year working for a local newspaper. Though it’s the first printing from this classic orange-and-white edition, it’s too tattered and stained to be worth anything. But I do love the knowledge that this has been read by a series of people over 53 years. That’s pretty cool.

Dickens is funny and open, delighting in revealing the details of her life as a “cub reporter”. This includes life in her rented room, and the relationships between the building’s various tenants, as well as the intricacies of a hokey local newspaper.

“I put away my things and tried not to feel bleak. My first night in that room stretched before me with too many hours, and I found that I was looking forward to going to work tomorrow. At the Munts’, I had often craved solitude, and dreaded hearing the creak of the stair and the whimsical tattoo on my door that meant Mrs Munt had come up for a pow-wow, but up here on the top floor, a stranger to the rest of the house, I felt unwanted and alone.”

She makes much of how the paper’s editor discourages true reportage, and instead has them write fluff pieces and endless lists of the names of people who attended this or that function. It clearly contrasts with her own love of detail, especially salacious or unusual detail.

“When I told the old man about…the apology, he put down his pen, sunk his neck deeper into his shoulders, looked at me like a bull, and then roared at me like a bull…I stood my ground, wondering whether it was the cold or Mr Pellet that made my legs feel weak. I was afraid that he would sack me. I had been thrown out of every job I had ever had in my life…suddenly he stopped in the middle of a sentence, leaving a vacuum in the air where his voice had been, gave me the sucked-in smile that made him look as if he had not got his teeth in, and muttered, ‘Silly bitch.’ “

There are occasions when Dickens’ light chatty tone contrasts oddly with the darker side of the lives around her. While she has the escape hatch of her well-off family back in London, many of the people around her are in meaner straits. She doesn’t show pity for them, or condescend in any way, simply recounts the details like the reporter her editor won’t let her be.

“The young man whispered how did I do, his grey, hungry face registering distress. He looked as if he had just suffered some tragedy which was still colouring all his actions and his attitude to the world. Maimie had merely told me he was a crackpot.”

Dickens came across as smart, funny and amiable, as well as being a notably strong independent woman for the 1940s and 50s. I’d love to read more of her work.

First published 1951 by Michael Joseph.

Source: Birthday present from my Mum.

Challenges: This counts towards the Classics Club.