See how the light needs shadows

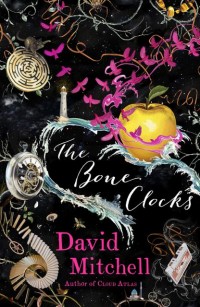

The Bone Clocks

by David Mitchell

It’s almost two weeks since I finished this book, and the more I reflect on it the higher it ranks in my esteem. It’s definitely a book that rewards giving it some thinking time.

If you’ve read any of Mitchell’s first three books (Ghostwritten, number9dream and Cloud Atlas) then this new release will feel familiar, and not just because of the direct references to characters, places and things in those books. This has actually been true of all Mitchell’s books but never quite so clearly as here. He has been world-building for five novels and now he’s capitalising on it with a glorious plot that combines the best of all that has gone before and throws in some brand new magic.

“Empires die, like all of us dancers in the strobe-lit dark. See how the light needs shadows. Look: wrinkles spread like mildew over our peachy sheen; beat-by-beat-by-beat-by-beat-by-beat-by-beat, varicose veins worm through plucked calves; torsos and breasts fatten and sag…as last year’s song hurtles into next year’s song and the year after that, and the dancers’ hairstyles frost, wither and fall in irradiated tufts…”

As I mentioned in my write-up of David Mitchell’s talk at Bristol Festival of Ideas last week, it would be very easy to spoil this plot by saying too much, so I’m going to try very hard not to do that.

The Bone Clocks opens with teenager Holly Sykes having a really rubbish day. She starts off pretty annoying, as indeed most teenagers are, but as events continue to go badly for her, I realised I must have warmed to her because I really did care how things were going to turn out. It’s 1984 on the Kent—Essex border and though Holly mentions punk music and the miners strike, she doesn’t need to because the setting is so very alive. Holly’s parents own a pub and in reading about it I pictured all those small town pubs from my own childhood.

There are hints of something fantastical in the background, that this isn’t just a realistic story about a 15-year-old who’s had a massive fight with her mam, but Mitchell keeps these hints simmering slowly. It’s a tactic that for me paid off brilliantly, as it kept me reading even when the narrator switched to a whole new person and story that once again I needed to warm up to.

“Grey comes in through the cracks, birdsong too, and the sound of a lorry passing overheard, and a sharp pain from a knocked ankle, and I’m crouching on the concrete ground of an underpass, just a few yards from the exit. A breeze that smells of car-fumes washes over my face, and it’s over, my daymare, my vision, my whatever-it-was, is over.”

As always, Mitchell’s style is very readable and enjoyable. There’s plenty of humour to balance out the occasionally tough topics addressed. But key to what makes this such a good read is that every character is a rounded, believable person and though there are a few clear heroes and villains, even they can’t be relied on to be wholly good or bad.

Published 2014 by Sceptre.

Source: Waterstones.