That we came out of it is a miracle

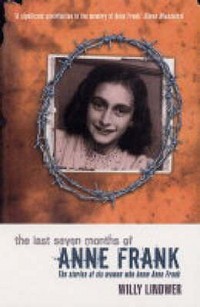

The Last Seven Months of Anne Frank

by Willy Lindwer

translated from Dutch by Alison Meersschaert

This was a tough read, in more ways than one, but it was also an enlightening and occasionally reaffirming one and I’m glad I have read it, so thank you H (who gave this to me as a present).

The title is to be honest misleading. This is not a book about Anne Frank. Rather, Anne Frank is a loose link between six Dutch women who tell their stories of the war and their experiences of concentration camps. More accurately what they have in common is that they were all arrested by the Nazis toward the end of the occupation of the Netherlands and taken to Westerbork, the Dutch transit camp, and from there were transported to Germany or Poland – to Auschwitz-Birkenau or to Bergen-Belsen, where they had contact with Anne Frank and some other members of her family. But for the most part Anne Frank’s role in this book is small. Really, these are the stories of six remarkable women who survived not only the war but also the Nazi concentration camps.

“I always envied the birds who could fly away. It seemed so fantastic to me to be able to fly, to go wherever you wanted to…You saw the birds everywhere; everywhere, there were birds, even in Auschwitz, even in Birkenau, and certainly in Bergen-Belsen, where it was so beautifully green and, at the same time, so gruesomely grey.”

— Rachel van Amerongen-Frankfoorder

Five of the women were, like the Frank family and other occupants of the Secret Annexe, arrested in summer 1944 and they met the Franks at Westerbork (only one of these five had half known the Franks beforehand, as she was at the Jewish Lyceum with Anne and Margot, but not in either of their classes). Their late arrests are the result of them having been in hiding. Three of them worked for the Resistance, helping others to hide, producing pamphlets or false papers, getting food or ration books to where they were needed, and they were arrested for this rather than for being Jewish (though they all had Jewish heritage).

The one story that is different from the others and most strongly adheres to the book’s title is that of Hannah Elisabeth Pick-Goslar, who had been a close friend of Anne Frank’s (in the diary she was originally given the pseudonym Lies Goosens but more recent editions use her childhood name Hanneli Goslar). She had a very similar background to Anne, born in Germany to a respected Jewish family in 1928, they moved to Amsterdam in 1933 as a result of anti-Jewish legislation and her father, a lawyer, set up a firm to advise refugees. She went to all the same schools as Anne and lived on the same street. Their families even went away together a few times (a postcard from one of those holidays is still on the wall of Anne’s room in Anne Frank House). As the Goslars were more religious, the Franks would go to them for Jewish holidays and Hannah would go to the Franks for national holidays (New Year and Sinterklaas). Hannah was one of the first to find out that the Franks had disappeared in 1942, but she was told the false story that the Franks had gone to Switzerland (where Otto Frank’s mother lived). Hannah writes about Anne as a good friend who was charming, beautiful, flirtatious and already considered a talented writer, but also as someone who was often sick and, as anyone who has read her diary knows, stubborn.

The Goslars were rounded up by the Nazis in June 1943 and thanks to political connections spent eight months in Westerbork before moving on to Bergen-Belsen, where they were kept in relative comfort (and stayed together as a family, which was extremely rare). When Hannah found out that Anne and Margot were in another camp on the site, separated from her by a barbed wire fence, she arranged to speak to Anne regularly and threw small packages of food over. It is clear from Hannah’s description that Anne’s side of the fence suffered far worse conditions and that Anne herself was desperately changed, had basically given up, but it is the testimonies of the other women in this book that really fill in how awful those conditions were.

Perhaps the most touching part of Hannah’s story comes after the war ended. She and her sister, now orphans aged 16 and 5, had returned to the Netherlands and were waiting to see who would adopt them, when Otto Frank showed up. He had seen their names on a list and travelled a long way to come and help them (considering he himself had only recently returned from Auschwitz). He took them first to Switzerland, where they had an uncle, and then helped Hannah apply for Israeli citizenship. They stayed in touch until he died and Hannah describes him as being like a father to her. Her words made me look on Otto Frank very differently, as a man who despite all his work around Anne’s diary actually did move on and find happiness and fulfilment.

The other five women’s stories are quite different, to be honest much darker, and I think it does them a disservice to make it all about Anne Frank. But to a certain extent this is acknowledged by the author’s introduction. Lindwer writes that he interviewed these women in the 1980s for a documentary about Anne Frank and that afterwards he felt it was a shame that such small snippets of their testimonies were used, because telling their stories had been so painful for them but also because they were important stories that deserved to be told. And so this book was born, containing the full interviews, serving (much like the Definitive Edition of Anne Frank’s diary) as a historical record more than as a work of art. It appears as though little has been edited, including facts, as there are multiple points on which these testimonies disagree, but then they are recalling the most painful experiences from 40 years later.

“Auschwitz was really the end of everything; the clay soil always with standing water; a huge quagmire without a sprig of green…There was nothing, nothing that looked alive, no flower, nothing, absolutely nothing. It was the end of everything, really the end. That we came out of it is a miracle. Very religious people understand it better than I do, because I never understood that a higher being – if one exists – could let all of this happen.”

— Lenie de Jong-van Naarden

They are clearly all amazing women and they deal with their past and their survival in different ways. My favourite story (and I’m guessing Lindwer agrees as it gets by far the most pages) is that of Janny Brandes-Brilleslijper who along with her husband Bob worked in the Resistance from 1939, and later at Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen volunteered as a nurse (she had some first aid training, though with the almost complete lack of supplies there wasn’t much could do for the sick except clean them with only a little water, but she did keep them company and sing songs). But they are all incredible stories and I learned so much, good and bad, from this book.

I suppose it is true that this has taught me more about Anne Frank, but mostly it has made me think of her death differently. It always seemed such hopelessly tragically bad luck that she was on the last Nazi prisoner transport from Holland, that she was moved from Auschwitz just weeks before it was liberated, that she died at Bergen-Belsen just weeks before that too was liberated, even that she died from illness and not from being selected for extermination. And of course it was tragic, but it was sadly not unusual. That last transport train carried more than 1000 people to Auschwitz, of whom just 127 survived the next eight months. The conditions at Bergen-Belsen were so bad that the majority of the inmates died of illness – typhus, starvation, pneumonia – shortly before or in the first few weeks after liberation. It was all awful and I am saddened and disturbed but also glad that I have learned a little more about it.

“I have told this because I want to make it very clear to a large number of people that all discrimination – whatever form it takes – is evil and that the world can go to pieces because of it…It only takes one person to say, ‘He isn’t as good as I am, because he has—’ You fill in the rest…We have to make sure that it will never happen again.”

— Janny Brandes-Brilleslijper

Die Laatste Zeben Maanden: Vrouwen in Het Spoor Van Anne Frank published 1988 by Gooi & Sticht.

This translation first published 1991 by Random House.

Source: This was a present from my friend H who bought it at Anne Frank House in Amsterdam.

I tried reading Anne Frank’s Diary when I was at school, but just couldn’t get into it. And I tried again about ten years ago after I’d visited Auschwitz – which had been a very moving experience for me, and I was quite motivated to have another go – but I still couldn’t get into it.

I’ve not heard of this book before now, but you’ve really sparked my interest. Thanks for reviewing it!

Martin I can see why Anne Frank’s diary might be tough to get into. She starts out as a slightly irritating over-confident 13-year-old. For me that’s part of the power of her story, but I can see that it’s not everyone’s cup of tea. This book is very different and possibly more relevant to an general interest in WWII.

I met Rachael and her husband, Eddy in Italy

in 1975. I remember them well. I tried to find them years ago but couldn’t. I am only now learning what they suffered. They were such kind, generous and loving people.

It sounds like they were remarkable women and having that as a title is a disservice to their own stories. hmm. I should read this one

http://www.thecuecard.com/