Her jittering soul paced on a stone slab in a grey room

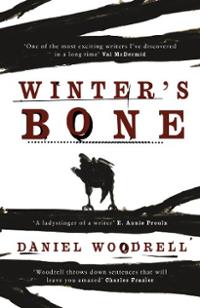

Winter’s Bone

by Daniel Woodrell

When this book was suggested for book club I had never heard of it or its author, but in the months since then both have cropped up repeatedly in book blogs and podcasts, always being showered with praise. Thankfully this didn’t happen so much that I had crazy high expectations, but maybe that wouldn’t have mattered because I completely loved it.

Someone (I think on the Slate Culture Gabfest) described Woodrell’s books as the new westerns, and while the storyline may seem a long way from cowboys and indians I can kind of see what he meant. It’s certainly a remote, lawless setting, or not lawless but with a different attitude to crime.

The book follows Ree, a teenage girl living in mountainous Missouri in a very poor, very small community. Her mother is mentally ill in some way – switched off and unresponsive – so Ree has left school to care for her mother and her two young brothers. Her father is absent, and his absence, and the need to find him, is the catalyst for the story.

“She smelled the frosty wet in the looming clouds, thought of her shadowed kitchen and lean cupboard, looked to the scant woodpile, shuddered…there was no gas for the chain saw so she’d be swinging the ax out back while winter blew into the valley and fell around her.”

Woodrell doesn’t shy away from the harsh, even brutal, reality of poverty, but somehow it is made bearable by the beauty of his language. The facts can take a while to become clear. In fact for the first few chapters I wasn’t sure when or where or what this story was. But that’s part of the point in a way. You can easily imagine that this small society in this area hasn’t changed much in 100 years. Everyone knows everyone else, and there is no privacy, but secrets can be kept if they are for the good of the community. And they might all survive because the men are cooking meth but there’s still a strong sense of honour, albeit an old-fashioned one.

“Ree’s grand hope was that these boys would not be dead to wonder by age twelve, dulled to life, empty of kindness, boiling with mean. So many Dolly kids were that way, ruined before they had chin hair, groomed to live outside square law and abide by the remorseless blood-soaked commandments that governed lives led outside square law…Sometimes when Ree fed Sonny and Harold oatmeal suppers they would cry, sit there spooning down oatmeal but crying for meat, eating all there was while crying for all there could be, become wailing little cyclones of want and need, and she would fear for them.”

Ree is a wonderful character. She’s so strong and driven by her responsibilities to her family, trying to be both father and mother while only on the brink of adulthood herself. When pain and possible death face her, she doesn’t flinch, but it’s not bravado, it’s just what she has to do, as if there is no option. Except the obvious option is staring her in the face – she’s offered hard drugs countless times and clearly wouldn’t be the first in this community to check out from reality that way. What she seems to choose instead is to try to distance herself from it all mentally.

“[Ree] pulled headphones from a pocket and clamped them over her ears, then turned on The Sounds of Tranquil Shores. While frosty bits gathered in her hair and on her shoulders she raised the volume of those ocean sounds. Ree often needed to inject herself with pleasant sounds, stab those sounds past the constant screeching, squalling hubbub regular life raised in her spirit, poke the soothing sounds past that racket and deep down where her jittering soul paced on a stone slab in a grey room.”

Someone at book club mentioned that the dialogue is slightly wrong for the modern era – people don’t talk like that. But I think I like that it’s slightly stylised. It adds to the timeless feeling of the story. Replace cooking meth with making moonshine and the rest still fits perfectly.

Woodrell uses the rural setting to great advantage, describing the woods and the winter in a way that reminded me of Frankenstein, with that idea of the sublime – the picturesque snow is juxtaposed with murderous cold and ice. But the descriptions are never overdone. In fact it’s a very slight book in which quite a lot happens.

“Keening blue wind was bringing weather back into the sky, dark clouds gathering at the edge of sight, carrying frosty wet for later.”

It should be a completely depressing story – indeed, some people at book club found it to be just that – and the facts of the story are indeed depressing, but the writing about these ugly lives is so gorgeous, almost magical, that I was left wanting more. Woodrell is very subtle and often only hints are given to what might be considered the key facts of the book, the possibility left dangling. But it’s not frustrating the way that could be with a less skilful writer.

Published 2006 by Hodder & Stoughton.

Source: Bought from Amazon.