A dictionary of loss

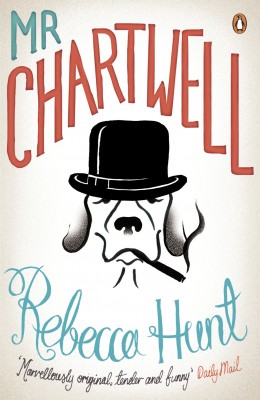

Mr Chartwell

by Rebecca Hunt

Since this book came out I had wanted to read it and finally persuaded my book club to read it for April – only to get the date of our meeting completely wrong and then get in a reading funk that meant it took me over two weeks to get through this thin little novel. I suspect this reflects unfairly on the book, because it never gripped me and yet I thought it was great.

The Mr Chartwell of the title is a large black dog who turns up on the doorstep of mousy librarian Esther and asks to rent her spare room. He is a bizarre combination of obnoxious human being and actual dog, but we gradually realise he is far more complicated than that. He is the physical manifestation of depression and shares out his attentions between Esther and a certain Winston Churchill.

Mr Chartwell, also known as Black Pat, is a repulsive character, as of course he should be. He irritates, demeans, distracts and tires out his victims. The setting is 1968, on the eve of Churchill’s retirement, so he is by now a dab hand at dealing with Black Pat’s visits, while Esther is completely new to it and takes most of the novel to figure out what is going on.

“A shirt dropped on the floor had developed a modest beauty, cultivating the painterly creases of a restaurant napkin. On the windowsill was a small balding plant. The magic of the late light made it gorgeous and exotic.

Esther stared from the bed, blind to these things. She lay on her side of the mattress. A hand explored the other side and it was a dictionary of loss. Up came the hand, disturbed by something disgusting. A tuft of collected fur. Over the bed, over everything.”

It really is a very original and interesting premise. It’s a clever way to depict depression and anxiety, giving an explanation that is at once nonsensical and yet makes a lot of sense. Several times, Black Pat comments how easy it is to give in to him, how he becomes a friend but of course he is a hated enemy so how can that be?

“She did nothing. The noble action was no action, for to discuss the dog would violate a guarded privacy, exhuming the bones of a family of secrets. It would be grave robbery. The dog’s genius was to make orphans of hope and brotherhood, and she was united with Churchill in their isolation.”

The characterisation is excellent. While it may seem clichéd to have a mousy librarian sinking into depression, Esther’s colleagues Beth and Corkbowl add a bit of liveliness and variety to the workplace. And Churchill’s brash, often aggressive conversations with Black Pat make an interesting contrast to Esther’s meek acceptance. I did find that Churchill spoke a little too much like a speech-maker, in wise aphorisms (except when he was swearing at Black Pat) but perhaps he really did speak like that. I would imagine Hunt did some research on him.

The quote on the front cover of my copy calls it “original, tender and funny” and I largely agree. It’s not laugh-out-loud funny but between the ridiculousness of the talking dog and gentle humour provided by characters in a more everyday way there is definitely some fun. And the issue of depression is certainly explored tenderly, carefully keeping its extreme depths at a distance, though they are certainly acknowledged. But really this is more about the lower-level, longer-lingering depression, a constant anxiety that has to be kept in check, the ongoing battle to get on with life.

“‘I aspire to have the smile of Tess of the D’Urbervilles…Hardy wrote that she had a smile like roses of snow.’

…Esther took in the exhibition of teeth. No roses of snow, it was a split haggis stuck with shards of coconut bark.”

First published 2010 by Fig Tree. Published in Penguin Books 2011.

Source: I think I bought this myself from an actual proper bookshop.

One Comments

Comments are closed.