Back to the classics

The Time Machine

by H G Wells

This is one of those greatly revered classics that made people look on with admiration while I was reading it, but actually isn’t a particularly hard read. It’s also not the most engaging, but it is full of Big Ideas.

And that’s both its strength and its weakness: this is an intellectual exercise more than it is a piece of entertainment. Wells was a scientist and drew on new exciting ideas in science to create a vision of the future that in its time would have been shocking, provocative, beyond credible and startlingly different from anything else, whereas now the science is widely known and accepted, what is left is a slightly bald political parable.

Somehow I came to this without really knowing the story. I mean, I’ve seen and read references to it (both Family Guy and Futurama have episodes devoted to this story) but I hadn’t seen any of the film versions or read a synopsis so some of it was a surprise to me.

The Time Traveller (as he is known throughout the book) has gathered together a meeting of London intellectuals to tell them about his new invention, the Time Machine. When they don’t believe him, he tells them to come back a week later when he will have seen the future, and it is his account of this trip to the future that forms the bulk of the novella. The format is slightly odd, in that an unnamed (indeed, un-anything) first person narrator attends these two meetings and records them in a manner somewhere between a journalist and a scientist, so that it’s fairly dry but with the occasional interjection of emotion.

The first thing that struck me was that this isn’t that familiar narrative of jumping a few years at a time into humanity’s future, finishing with a quick trip to the end of the world. The Time Traveller jumps straight beyond the human race as we know it, to the year 802,701 AD, and most of the story is set in that one time (though there are a couple of further jumps forward). In this future, human beings have evolved into two distinct species – the gentle, childlike, darkness-fearing Eloi and the ominous, monstrous-looking, light-fearing Morlocks. The Time Traveller can only conjecture how these races came to be and recounts more than one theory that he subsequently rejected upon further observation.

This means that we cannot necessarily trust the Time Traveller’s interpretation, and indeed his descriptions are a little sparse. Can we be sure that these creatures are all that human-like? When he acquires a female Eloi companion he tells us that she is called Weena and she is really the only character to have a name, almost as if he is trying a little too hard to humanise her.

Without being shocked by the conceit of suggesting that mankind might one day evolve, the political allegory seems a little heavy-handed. Wells paints an extreme end to the widening gap between rich and poor, with the idle rich becoming the Eloi and the industrial working class becoming the Morlocks. There is also an interesting point about both having lost the need for intellectual capacity, because “Only those animals partake of intelligence that have to meet a huge variety of needs and dangers.”

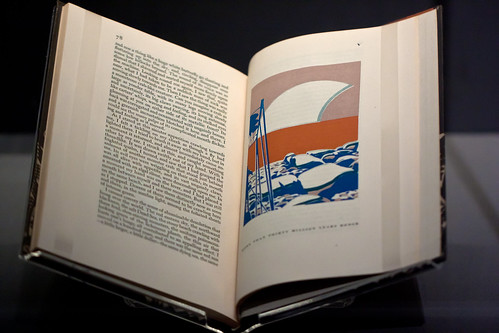

I will admit I was more scientifically interested in the descriptions of the further future, with geological timescales having passed, where Wells describes not only an ice age but also changes to the Sun, the Earth’s orbit, various stars, the Moon, tides, even other planets in our solar system. He was building on recent discoveries in physics and this description was no doubt just as revolutionary (and possibly just as provocative) as his evolved humanoids, but it is also beautiful. The story of the Eloi and the Morlocks is essentially a sad one but the continuation of Earth through immense changes in the solar system is somehow uplifting and inspirational.

As a story, I was a little disappointed in The Time Machine – I didn’t find it engaging, the characters are deliberately insubstantial and many of the ideas no longer appear original or daring. However, it is still a clever, inventive take on the travellers’ accounts that it is built on.

First published 1895.