Hunting for metaphors which might convey something

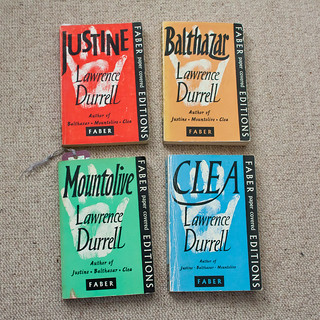

The Alexandria Quartet

Book 4: Clea

by Lawrence Durrell

And so at last I have finished the quartet. Was it a fitting end, full of vagueness and mystery? Did the poetic unreliable narrator return, both as a narrator and to Alexandria itself?

Well, the answer to question two (both parts) is yes but to question one…I’d hazard no. The series began, in Justine, with a lot of vagueness, events in uncertain order and a lot was left unsaid. As the Quartet proceeded, the narrative got clearer and clearer until this book, even though it is once again narrated by Darley, who was previously so unreliable, was perfectly straightforward and linear. I mean, there were memories and extracts from old letters, but they were clearly signposted as such. To be honest I found this disappointing, though it was good to get closure on all the characters and storylines at last.

Which is not to say that the writing in this book is less good than it has been previously. In fact, I have bookmarked more quotable passages than ever. But as a story it didn’t grip me. Which is odd because there was a lot going on in this book. Darley has been called back to Alexandria from his Greek island to return the child he has been looking after to her true father. World War II has finally got under way and Alexandria has not escaped unscathed. Mountolive (the British Ambassador to Egypt) finds Darley a job in the censorship department of the War Office, which is a perfect statement on his narrative. No mention is made of Darley ever having been expected to fight, despite his being a British citizen of, I assumed, good health and young age, but I don’t know what the situation was for ex-pats.

And so, until the end of the war and a short time afterward, Darley catches up with the lives of his old friends, makes sure the girl settles in with her new parents and discovers more details about his previous stay in Alexandria that once again force him to re-evaluate the truth. Clea is, as ever, everyone’s friend and confidante, and a cheery one at that, so through her we hear the little anecdotes that people really do tell about their friends, particularly those who have died. She is a good influence on Darley, encouraging him to not just face the truth but actively seek it. When one friend asks Darley how his writing is going, he replies:

“It has stopped…I somehow can’t match the truth to the illusions which are necessary to art without the gap showing…”

The picture of a city at war is hauntingly real. A lot of the time, Alexandria is on the outskirts of the war, the place where soldiers come on leave from the desert frontlines, but it is for a short time bombarded and the harbour is full of warships rather than pleasure boats.

“How had things changed? It was not danger, then, but a less easily analysable quality which made the notion of war distinctive; a sensation of some change in the specific gravity of things. It was as if the oxygen content of the air we breathed were being steadily, invisibly reduced day by day…”

One thing I found a little strange was that one longish chapter takes the form of an essay written by (Darley’s former flatmate) Pursewarden years earlier after a series of conversations with Darley about literature. It is eloquent and interesting and so, so quotable (“Words being what they are, people being what they are, perhaps it would be better always to say the opposite of what one means”) but it perhaps went on a little long and broke up the story more than necessary for its purpose: making Darley realise he had misjudged Pursewarden.

Despite the apparent changes in Darley, perhaps he is still unreliable, because he still manages to fool himself and he repeatedly declares that he is done with writing yet he narrates as if he is writing it down:

“I am hunting for metaphors which might convey something of the piercing happiness too seldom granted to those who love; but words, which were first invented against despair, are too crude to mirror the properties of something so profoundly at peace with itself…”

And lest all the revelations and clarifications of this book fool us into thinking we are here learning the absolute final truth about these characters, we have this pearl from the wise old doctor Balthazar:

“When one casts around the fields of so-called knowledge which we have partially opened up one is conscious that there may well be whole areas of darkness which may belong to the Paracelsian regions—the submerged part of the iceberg of knowledge.”

So on the whole it was a fitting end to the Quartet. It made me laugh, it made me sad. It has a surprisingly modern attitude to sex, love and homosexuality (though the characters do not necessarily have modern attitudes) and I can now go and have a look at the last discussion of the Guardian Reading Group without having the story spoiled for me!

First published 1960 by Faber & Faber.

N.B. It’s too late now to join in the Guardian Reading Group discussion about this book but you can still listen to the Guardian Books podcast about Lawrence Durrell at 100. It discusses and quotes heavily from The Alexandria Quartet and is well worth checking out.

See also: my reviews of

Book 1: Justine

Book 2: Balthazar

Book 3: Mountolive

I must get back to reading the quartet. I have never gotten past Justine and am looking forward to it! Thanks for the excellent comments on the books.

Harvee Glad to hear you’re going back to them. I’m pretty certain I will re-read these books in 10 years or so. They deserve re-reading.