Life is nothing like a story in a book

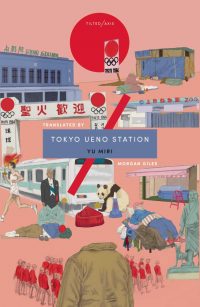

Tokyo Ueno Station

Tokyo Ueno Station

by Yu Miri

translated from Japanese by Morgan Giles

This is an astonishing novella, packing so much insight and commentary and humanity into so few pages. And it taught me snippets of history as well. I’m really not sure how Yu managed it.

The tale is narrated by Kazu, an old man who has spent the last few years homeless, living in Ueno Park in central Tokyo. He tells his life story, but not linearly. An overheard conversation will remind him of his son. A piece of rubbish will remind him of a friend who died. A rain storm will remind him of a certain day in the past. And so on.

Kazu is an ordinary man, which is of course the whole point. He didn’t become homeless because he’s a junkie or had been in prison. Yu doesn’t spell out the reason he ended up in Ueno Park, but as we see his long lonely life getting sadder and lonelier, we can fill in some of the gaps.

“I used to think life was like a book: you turn the first page, and there’s the next, and as you go on turning page after page, eventually you reach the last one. But life is nothing like a story in a book. There may be words, and the pages may be numbered, but there is no plot. There may be an ending, but there is no end.”

Kazu spent his working life living far away from his family, travelling to where construction work was needed and sending money home to his wife and two children in Fukushima. When he retired and moved back in with his wife, they were near strangers. In some ways he had a closer relationship with a hostess at a bar he frequented in Hirosaki for the 10 years he worked there.

Two things loom over the narrative. The first is the 2011 tsunami, which destroyed much of the Fukushima region. Kazu doesn’t tell the detail of how this affected him until near the end of the book, but knowing where he is from it is inevitable that this is one of his scars. The second is Kazu’s weird link to the emperor. They were born in the same year (1933) and had their first son on the same day. And yet their lives could not be more different.

“I spent my life thinking about people who were not there. People who were not with me, people who were no longer in this world. I never felt entitled to speak of the absent to those who were there, even to my own family. I could not alleviate the weight of my memories of those who were absent by speaking of them.”

Dotted through the book are details of how the homeless in Ueno Park are being moved into smaller and smaller areas, further from the main public thoroughfares. It’s a very big park, home to Tokyo’s zoo, science museum and three other museums as well as a shrine, a temple and a large pond. I remember visiting Ueno Park and being impressed by how much was packed in there. But I didn’t see the homeless, perhaps because the homeless become invisible to us if we’re not looking specifically to see them.

Yu does an amazing job of shining a light on the very people we ignore. The prose manages to be poetic and simple, gentle and angry. There are moments of humour, fascinating insights and beautiful descriptions, but most of all there is pathos. This book will make you sad, but it will also make you look twice when you walk around a city.

JR Ueno-eki Koen-guchi published 2014 by Kawade Shobo Shinsha.

This translation published 2019 by Tilted Axis Press.

Source: Storysmith, Bristol.