They didn’t look for long, it was more a practice series of glances

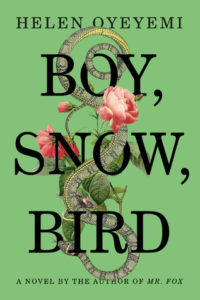

Boy, Snow, Bird

Boy, Snow, Bird

by Helen Oyeyemi

I remember reading Oyeyemi’s debut novel The Icarus Girl in 2005. I was simultaneously highly impressed by her writing, and jealous that someone so young was so talented. (I was at the time trying to sell my own debut novel. It was terrible. I do not blame the publishers and agents who rejected it.) Icarus Girl and Oyeyemi’s 2011 novel Mr Fox both received a rare five-star rating from me, and Boy, Snow, Bird followed suit. Oyeyemi is truly brilliant.

Boy, the lead character, runs away from her abusive father in 1950s New York and sets up home in a small New England town called Flax Hill. She takes a series of short-term jobs, never really fitting in until she marries a local man. Finally she has found safety and security. Boy finds herself stepmother to the beautiful, delicate Snow, a young girl she loves dearly until she finds herself pregnant with her own daughter, Bird.

“I was on shaky terms with [Flax Hill] for the first few months. Neither of us was sure whether or not I genuinely intended to stick around. And so the town misbehaved a little, collapsing when I went to sleep and reassembling in the morning in a slapdash manner.”

This is an imaginative, lateral take on the Snow White fairytale. It’s far from a straight retelling. Boy is our heroine – she’s a funny, complex woman, an escapee from abuse – so how can she be the “evil stepmother” of the old tale? But then this is itself a comment on perspective – in the stepmother’s own eyes, of course she isn’t evil.

There is a recurring motif of mirrors – again, playing into the fairytale but the mirrors don’t talk here. Mirrors are of course an emblem of self-image, self-knowledge and perspective – all key themes here. Along with secrets, emotional and physical abuse, escape/banishment and concepts of beauty.

“They both turned to me and went on a looking spree. I left them to it and wished I could sail over their heads and into the acid blue sky. They didn’t look for long, it was more a practice series of glances; they knew what they were looking for and seemed to find it. It was a wonder there was anything left by the time they were through looking.”

There are some big reveals in this novel that I would count as spoilers but it’s hard to discuss the book further without talking about them. So I’m going to do a rare spoiler warning here. Do not read further if you haven’t read the book and want to.

*** Spoilers ahead ***

The first twist in the story is that a big chunk of it is about race. Boy’s daughter is dark-skinned, revealing her husband Arturo and his family’s long-kept secret: they are light-skinned African-Americans who have a tradition of sending away their darker-skinned children to maintain their ability to pass as white. Boy faces a tough decision and she makes it without hesitation. It’s a choice that will reverberate through the years and uncover more about her family and her husband’s family.

What I liked about Oyeyemi’s take was that she didn’t judge Arturo’s family or Boy for their decisions. Their choices could be interpreted as based on artificial constructs of beauty. But it’s also about social history, escaping from slavery (literally and figuratively) and the reality of racial tensions in the US.

“What you don’t understand is that we’re being kept down out there. All the way down. In my town you couldn’t vote unless you passed a literacy test. How does that stop colored folks from voting, you ask? You didn’t see what the colored school was like, how big the classes were. The teachers did what they could, but half my male cousins could hardly read. They lost patience before the girls did. No matter how literate a colored man was, there was always some excuse to whip him.”

[I’m currently reading Paul Theroux’s travel book Deep South and it is eye-opening and disturbing to hear how many schools in the southern USA didn’t really integrate until the 1970s, 80s or even 90s. Suddenly Arturo’s family don’t seem so crazy or misguided.]

Even Boy’s father is given some depth and character, so that he is not merely a dark shadow in her past. His reveal is saved for the very end of the book, so I won’t discuss it even here, but it’s testament to Oyeyemi that it is both foreshadowed from the start and a key theme, while also being completely immaterial. He’s still an abusive father and Boy was right to leave him.

*** End spoilers ***

Oyeyemi’s writing is a curious mixture of dreamlike metaphor and blunt reality. Boy’s narration in the first section is sometimes evasive, sometimes naive. It’s writing that evokes a love of words – does that make sense? I love it, obviously, and fully intend to fill in the gaps in my reading of her back catalogue.

Published 2014 by Riverhead.

Source: Beerwolf Books, Falmouth.