Like a vision seen in a dream and scarce remembered

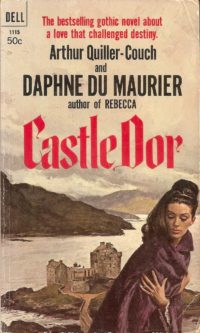

Castle Dor

Castle Dor

by Arthur Quiller-Couch and Daphne du Maurier

Well what a contrast to my previous read. After lingering for two weeks over The Evenings, I raced through Castle Dor in 24 hours. Was it a case of the right book at the right time, or is it just a cracking good read? It is Daphne, after all.

Except that it’s only sort-of Daphne. This book was started by Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch (better known to many by his pen name Q), who Daphne knew a little as her near-neighbour in Fowey, but he was much older than her, so it was his daughter Foy (named for their beloved home town) who became a close friend of Daphne’s. When Q died in 1944 he left behind one final unpublished work of fiction: the first half of a novel retelling the story of Tristan and Iseult, set in 19th-century Cornwall. Some 15 years later, his daughter Foy persuaded Daphne that she was the perfect person to finish the book.

Knowing that in advance, it is certainly possible to spot the signs that different hands start and end the novel. But it is skilfully done, with no obvious seam. (Apparently Q’s manuscript was left mid-chapter, even.) I can tell you that the opening chapters felt more flowery and more scholarly than any Daphne du Maurier book I’ve read (and I’ve read a lot of them now). And the closing chapters had a touch of the supernatural, even spiritualism, that felt very Daphne and certainly hadn’t been so prominent in the book. But the join between the two felt entirely gradual and invisible.

The classical romance is retold starring young and beautiful Linnet Lewarne, married to a much older man, and Amyot Trestane, a Breton sailor who turns up on her doorstep selling onions. She saves him from a cruel master and he saves her from runaway horses, not to mention a life without love. But this is not just their story. It is as much that of Dr Carfax, amateur local historian and etymologist whose fascination with the idea that the legend of Tristan and Iseult might have its roots in his home town leads him to notice the young lovers’ secret and try to prevent them sharing the tragic ending of the ancient tale.

It is a wonderful story beautifully told. There were times when I wondered if Carfax’s studies too obviously signposted the Tristan and Iseult link, but in the end I think it was the right call. Besides enabling the foreshadowing of very small details that the average person is unlikely to know of the original story, it also allowed for some interesting discussion of the different historical texts and the variations between them, therefore keeping several options open for the fates of Linnet and Amyot.

“He faced her across the glow of the fire and took the glass, dazedly, looking into her elfish eyes. Having drunk he passed it back to her and she too drank.

He fell back on his elbow. There was a spurt of flame as she tossed the dregs of the glass upon the embers. She also leant back her shoulders pillowed upon a cushion of moss. The dying fire faded between them. Fair and alluring though she was, Amyot dared not cross the fire to touch her. A constriction of the heart held him.”

I remember reading in Letters from Menabilly: Portrait of a Friendship Daphne’s fears and concerns about taking on this project. I also think that Foy Quiller-Couch was completely right to choose Daphne for it. Though her writing style differed a little from Q’s, they shared a love for Cornwall and an approach to genre-fluidity that are both key here. Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch was as much a scholar as an author, and a classical scholar at that. While Daphne was no stranger to research for her own books, this is a different beast and must have been a real challenge that she more than rose to.

Despite being dismissed by some as a romantic novelist, I have always thought that Daphne is much more than that label implies. In fact, in most of her works romance is the least of the themes, far behind jealousy, revenge, unhappiness and all those other grand themes of life. Q famously wrote that labels such as “classical” and “romantic” are meaningless, that writers hone their craft and write their own individual works. Which for me makes the pairing an excellent choice to retell an ancient tragic love story, because the result is a book about people and their fallibility – an endlessly rich subject.

“Linnet advanced from the window, from where she had been watching the scene below, and in the half-light it seemed to the doctor that her beauty, of which he was always well aware, had for the first time a curiously uncanny quality, like a vision seen in a dream and scarce remembered, while the faintly mocking smile with which she greeted him brought a disquiet and discomfort too.”

That said, I did have some quibbles. And these might be a bit spoilery, so skip this paragraph if you want to remain spoiler-free. My biggest gripe is the supernatural theme that Linnet and Amyot are somehow possessed by the ghosts of Tristan and Iseult, doomed to play out the same story. If this had been simply hinted at, fair enough, but it was spelled out several times and frankly got a little tedious. The link between the pairs of lovers was clear enough without there needing to be a literal possession. Similarly, Dr Carfax’s research is at first all about the idea that generations of scholars have disagreed over the geographical setting of Tristan and Iseult, and his theory that the true setting is his own corner of Cornwall, on the rivers Fal and Par. He and a research buddy gradually discover that many of their neighbours, including of course all the key players in the story, are direct descendants of characters from the ancient tale, which for me was again a step too far.

Both these things are more prominent in the latter half of the book, and therefore more due to Daphne. That said, I think in her half the characters become a little more real and the dialogue is certainly more natural. I would hazard a guess that her respect for Q, combined with the nature of the commission, meant that she made few edits to the original manuscript. And yet it is only on reflection that the differences between the two halves are apparent. I’m certainly curious now what I would think of Q’s previous novels.

Quibbles and all, this really is a cracking good read.

First published 1962 by J M Dent & Sons.

Source: Enjoy! Fowey – a tourist information/bookshop in Fowey, Cornwall.