Great swaths of her life were white space to her husband

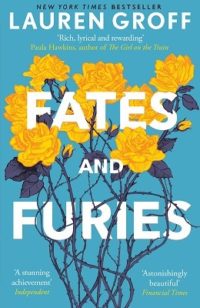

Fates and Furies

Fates and Furies

by Lauren Groff

This is some ways the very epitome of “literary fiction” and yet it defied my expectations many times. I had expected to like it, after thoroughly enjoying Groff’s previous novel The Monsters of Templeton. This is quite different, but once again, really good.

It’s the story of a marriage, that of Lotto and Mathilde. What makes this book different is that the entire marriage is told from Lotto’s perspective, and then from Mathilde’s. The narrative voice, revealed occasionally in square-bracketed asides, is first the Fates (for Lotto) and then the Furies (for Mathilde). As you might guess from that, Lotto’s story is all about his fate: who he is meant to become, what is meant to achieve. Mathilde’s story is largely about her fury, how it drives her.

“The Buddha laughed in silence from the mantelpiece. Around him, a lushness of poinsettias. Below, a fire Lotto had dared to make out of sticks collected from the park. Later, there would be a chimney fire, a sound of wind like a rushing freight train, and the trucks arriving in the night.”

As adults, Lotto and Mathilde are almost clichés – the selfish artist and his self-sacrificing wife. But Lotto is the warm, cuddly, beloved one, while Mathilde is cold, a hardass who gets things done. White, middle class, educated, they marry young, within weeks of meeting, and the early chapters recount a series of parties at their New York City apartment. The group of friends and family ebbs and flows as the years pass. New partners, children, fall-outs and break-ups surround the central couple.

Lotto and Mathilde’s childhoods are far from ordinary. There’s a fairytale-like oddness to both their backgrounds. Lotto’s mother, for years a mermaid in a theme park, could have stepped straight out of a Tim Burton film. Groff sketches this background quickly, in just a few pages, but picking out just the right details to make it engrossing.

“Great swaths of her life were white space to her husband. What she did not tell him balanced neatly with what she did. Still, there are untruths made of words and untruths made of silences, and she had only ever lied to Lotto in what she never said.”

Inevitably, the second half of the book is the revelatory part, where we learn the hidden secrets, the things that were not as they seemed. Groff manages to not go down the expected paths with this. The secrets the couple had kept are both good and bad, small and large, and reveal more about both of them as people. But most of all, the secrets are not the whole point.

Groff’s writing is somehow both lyrical and concise. She reveals the complex and extraordinary in the ordinary and everyday. It’s a beautiful, often sad, sometimes sweet story. It’s also a very adult story, in every sense of the word. I suspect I would not have appreciated this book 15 years ago (had it existed) and even now it took a little time to grow on me, but by the end I was a thorough convert.

“It occurred to her then that life was conical in shape, the past broadening beyond the sharp point of the lived moment. The more life you had, the more the base expanded, so that the wounds and treasons that were nearly imperceptible when they happened stretched like tiny dots on a balloon slowly blown up. A speck on the slender child grows into a gross deformity in the adult, inescapable, ragged at the edges.”

Published 2015 by Penguin Random House.

Source: Amazon.