There were no slow degrees of consciousness

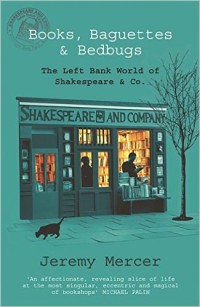

Books, Baguettes and Bedbugs

Books, Baguettes and Bedbugs

by Jeremy Mercer

I’ve seen this book recommended by lots of people over the years, but I must admit, all I knew about it was that it’s about the Shakespeare and Company bookshop in Paris, a tourist attraction I’ve never visited, and knew of only as a famous bookshop associated with some famous authors and artists. So I learned a lot, and completely fell in love with the shop and its story.

I’ve been to Paris twice, and travelled through it another two or three times, and it’s a little crazy that a famous English-language bookshop near the city centre wasn’t on my list of attractions to visit. It certainly will be next time, though it won’t be quite the same shop that Mercer describes.

First, I learned that the current incarnation of the bookshop, on Rue de la Bûcherie, is not the same as the first bookshop by that name, which was opened and run by Sylvia Beach from 1919 until 1940. That shop had its own wonderful history with colourful characters who have popped up in various things I’ve read, but Mercer for the most part skips past all that to the second Shakespeare and Company bookshop, which was opened in 1951 by George Whitman. He originally called his shop Le Mistral, but changed it in 1964 to Shakespeare and Company in tribute to Sylvia Beach, following her death.

Mercer combines this larger history of Shakespeare and Company with his personal tale of living at the bookshop for several months in 2000. He is a Canadian journalist who had been a successful crime reporter, but had got into trouble by naming a source and, fearing for his life, ran away to Paris, as writers are wont to do. He had almost run out of money when he visited the bookshop and was invited to one of their legendary Sunday tea parties. There, he learned that George Whitman invited writers and artists to live in the shop, making it as much a commune as a business (possibly more of a commune, in fact, considering George’s business sense and his being a genuine card-carrying Communist). Mercer wanted in.

“I woke up straight. The instant my eyes opened, everything felt sharp and clear, as if I’d finished a wind sprint or stepped from a frothing sea. I’d always been one to play with snooze buttons, lolling in bed and rationalizing being ten, twenty, thirty minutes late for work or school. But that first morning at the bookstore, there were no slow degrees of consciousness or seductive fingers of sleep. I was alive”

George’s conditions for “Tumbleweeds“, as he called his guests (and considered himself to have been on his own arrival in Paris), were threefold: to read a book a day, help out in the shop and write a single-page autobiography for his archives. Mercer was given one extra condition: to evict Simon, an antisocial poet who’d been living in the antiquarian room for several years and had started to prevent customers from getting in.

Mercer threw himself into all this with gusto. He befriended his fellow Tumbleweeds and learned how to live for pennies by making use of public showers, market-day leftovers and a nearby student refectory. Importantly, he became close to George himself and became privy to details about the shop’s precarious future and George’s past.

“We were all nearly penniless, mostly homeless, and without proper residence papers or health insurance in a foreign country. Though the whiteness of our skin protected us from the harassment North Africans and other more visible illegal immigrants suffered, one major incident or brush with police and our fairy-tale lives in Paris would come to an end.”

This is all key to the story that Mercer is able to weave, so that it’s about the shop’s redemption as much as his own. He’s a great storyteller and though he’s not the only Tumbleweed to have written about his experience, I can see why his book is one of, if not the, most famous example. He’s honest about his own failings, which is probably best as the picture he paints of his younger self is a far less attractive prospect.

Mercer’s afterword acknowledges that the shop changed a lot in the years immediately following his stay there. From a look at its website it has changed a lot more since, and I suspect it’s doing rather better financially. I’m a little sad that when I was in Paris in 1997 and 1999 I could have seen the incarnation of the shop Mercer describes, but I’m telling myself that as a teenager I wouldn’t have appreciated it anyway.

Incidentally, this book’s original title in North America was Time was Soft There, which makes more sense than its UK title because there are zero bedbugs in this book. Lots of books, and quite a few (mostly stale) baguettes, but no bedbugs. Weird decision, that.

First published 2005 by St Martin’s Press.

Source: Christmas present from my Dad.