The poem is an extraordinary mechanism

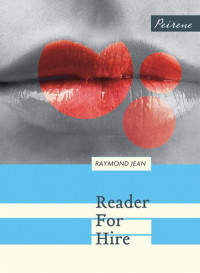

Reader for Hire

Reader for Hire

by Raymond Jean

translated from French by Adriana Hunter

This is an unusual book, difficult to pin down. It’s comedic bordering on farce, it’s sensual to the point of erotica, it’s intellectual veering dangerously close to literary criticism. All of which can be ignored if you just want a good story to enjoy, but you will need an open mind for this one.

It was her friend Françoise’s idea, but Marie-Constance quickly finds herself having to fight for it. She places an ad in the local paper offering her services as a reader, because her voice is her greatest asset. The newspaper man thinks the advert sounds suspicious. Her old university tutor thinks she will attract the wrong sort. Her husband alone is indifferent.

Marie-Constance’s first client is a paraplegic teenager who initially seems more interested in the length of her skirt than the classic short story she has chosen to read him, a choice that ends in near disaster. Her second client is an elderly woman with cataracts who only wants to read Marx, which bores Marie-Constance to tears. The third is an attractive newly divorced executive who claims he only wants a crash course in literature so that he can appear more cultured. Each new opportunity seems to bring new problems and soon Marie-Constance is on first-name terms with the local police chief.

“I’m oddly transported by my own voice too and, as I read, I feel as if the poem is an extraordinary mechanism, a fantastical clockwork machine, and all its component parts, its every articulation, could be laid bare, if that was what I wanted.”

The term “unreliable narrator” might be a cliché but there are certainly reasons to think Marie-Constance is being dishonest, or at least disingenuous. She makes a point of wearing short dresses for her teenage client under the pretence that she thinks he appreciates the fabrics. She claims her marriage is happy and yet on page one admits that the most attractive part of Françoise’s proposal is the bachelors who might respond to her ad. She claims to be offended by the newspaper man who hints that this is what her advert is really about, and while she does try for a while to turn this unusual concept into a genuine job, sex is clearly what she is most interested in.

The exact text of her advert is “Young woman available to read to you in your own home. Works of literature, non-fiction, any sort of book you like.” You can see how it might be misconstrued. The newspaper man tries to persuade Marie-Constance to change “young woman” to “person”, which is of course a horrible replacement, but it does mean she has the opportunity to make a more elegant alteration, which she not only disregards, but claims to not see any problem. This whole episode, at the very start of the story, indicates an awareness of the importance of precision, how just one or two words can drastically change a sentence or paragraph, and let me know that I was in good hands.

So is Marie-Constance just a bored housewife? She certainly doesn’t seem to need the money, and while Jean at no point belittles his heroine, I did get the impression that he was skewering a certain kind of affluent middle-class ennui. Every problem that Marie-Constance encounters need not have become a problem if she had confronted it differently, which suggests that she is in fact seeking out the thrill of adventure. In this aspect, the novel betrays its 1980s origin, but aside from this the story could be from any decade in the last 70 years, perhaps even earlier.

For such a short book, this certainly got me thinking and I genuinely enjoyed the ride it took me on, but I also found it a little lacking. It’s comedy but it’s not that funny. Though it celebrates literature and reading, the language wasn’t especially moving or transporting, but that’s not to say it’s at all badly written. It’s an engaging novel and it does demonstrate a clear love for reading aloud. It’s an activity with the potential to be very sensual and, though he’s not the first to spot this, Jean has done a lovely job of extrapolating this concept into an unlikely and yet somehow believable story.

“I have the peculiar feeling that there really is an angel among us in person…It’s hovering, it’s between us, above us, an insubstantial presence and yet it’s an astonishing physical reality, a ruffling feeling, a sound of wings, impalpable and silky, in my ear, against my neck, on my skin, and a thin beam of light shining, quivering among us.”

La Lectrice published 1986 by Actes Sud.

This translation published June 2015 by Peirene Press.

Source: I subscribe to the publisher.