Most stories about the past have an element of pain

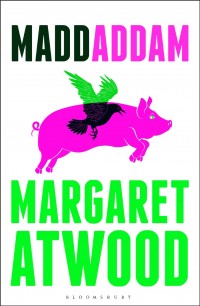

Maddaddam

by Margaret Atwood

This is the third instalment in Atwood’s Maddaddam trilogy, following on from Oryx and Crake and The Year of the Flood, so this may review contain spoilers for the previous two books. Once again we are in a post-apocalyptic future that feels at once entirely alien and all too possible.

Like the previous two books, this novel looks back to a pre-“flood” story, while also dealing with the post-flood present, but there is more of the present than there has been previously, because really here that’s the emphasis – is this the new way of things? Can humanity survive and if so, how?

The pre-flood story that is slotted into the narrative is mostly about Zeb, who was a fairly minor character in The Year of the Flood but turns out to be an important link between everyone and everything else. However, this wasn’t clear at first and it seemed strange that the flashbacks should linger for so long on him. In particular, there’s an early episode about him having killed a bear that frankly dragged a bit. But once the pace of his back story picked up and some of the links to the wider story became clear, I did enjoy getting to see all the same events again from yet another fresh perspective.

“Will this be a painful story? It’s likely: most stories about the past have an element of pain in them, now that the past has been ruptured so violently, so irreparably. But not, surely, for the first time in human history. How many others have stood in this place? Left behind, with all gone, all swept away.”

The post-flood story is less contemplative than it had been in the previous two books; in fact there’s quite a bit of action. The plague-surviving humans (a mix of God’s Gardeners and Maddaddamites) and the Crakers are learning to understand each other and co-exist, and this raises a lot of issues. Are the Crakers human – and indeed, what is the nature of humanity? Are culture and storytelling innate or taught? Can/should the humans protect the Crakers from bad stuff and teach them knowledge, or should their innocence be maintained as Crake intended? Are the Crakers the only hope for the future?

“He could sense words rising from him, burning away in the sun. Soon he’d be wordless, and then would he still be able to think? No and yes, yes and no. He’d be up against it, up against everything that filled the space he was moving through, with no glass pane of language coming between him and not-him.”

One of the recurring scenes in this book is the Crakers’ story time. The Crakers insist on the daily ritual that Jimmy/Snowman began in Oryx and Crake, and though the storyteller now varies, the style is the same – a somewhat stilted, sanitised version of the truth. These sections are at first odd, irritating even, but gradually become familiar and often humorous, and finally they become the backbone of the whole novel.

“In the beginning, you lived inside the Egg. That is where Crake made you. Yes, good, kind Crake. Please stop singing or I can’t go on with the story…All around the Egg was the chaos, with many, many people who were not like you. Because they had an extra skin. That skin is called clothes.”

This was a satisfying end to the trilogy but it didn’t quite match up to the high point of The Year of the Flood for me.

Published 2013 by Bloomsbury.

Source: Bought at an author event run as part of Bristol Festival of Ideas.

I recently read Oryx and Crake and wondered if it was worth going onward. It appears it is. Others have also said Year of the Flood is the best of the 3. Here’s my thoughts on the first one:

http://www.thecuecard.com/node/802

Susan Yes, definitely worth continuing on to Year of the Flood, and then if you like that you’ll want to read Maddaddam for the closure!